In the course of her career and research into workplace behavior, Nicole Jones Young has noticed that some managers recognize the work of the loudest, most confident and, sometimes, the most well-heeled person in the room.

Most people have had at least one colleague with a sense of privilege who likes to speak first, she says, and that can often drown out other voices in the room. “This behavior may make it difficult for those of lower social classes to successfully interject and navigate the higher ranks within an organization,” Jones Young says.

Individuals with relatively high social class are more overconfident and appear more competent to others. This helps them attain higher-earning jobs.

Jones Young, an assistant professor of organizational behavior at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa., is fascinated by how a person’s socio-economic background translates to how they are perceived at work. Often times, she says, they are perceived favorably. She is amazed at how some people act like they’re destined for the corner office.

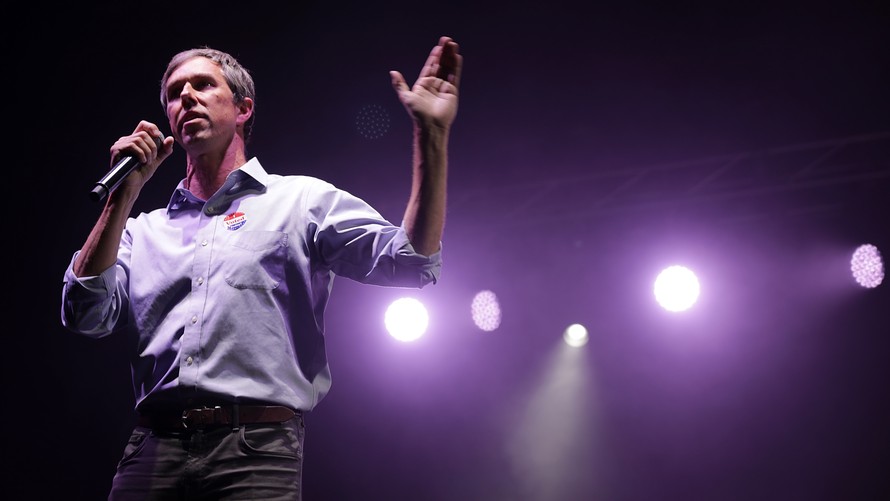

Others say they’re destined for the highest office in the land. Democratic presidential contender Beto O’Rourke, who attended Columbia University in New York, told the April 2019 issue of Vanity Fair magazine, “Man, I’m just born to be in it, and want to do everything I humanly can for this country at this moment.” (O’Rourke later said he could have chosen his words more judiciously, and said he was referring to his calling to public service.)

Not everyone has the innate ability to eye an opportunity with that kind of confidence or, some might say, entitlement. That ambition and confidence is likely instilled in people at a young age. Jones Young says, in her experience, they often happen to be from privileged backgrounds, and that can create a structural and cultural imbalance in the workplace.

“How do managers or those in positions of power acknowledge these differences and create an environment where all employees have an opportunity to showcase their talents and perspectives?” she says.

Nicole Jones Young

Nicole Jones Young

Recommended: Why so many primary-care doctors across America are closing their doors

Jones has mulled that question while reading the many conclusions from a series of studies published Monday by researchers from Stanford University and the University of Virginia in the peer-reviewed Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Interpersonal Relations and Group Processes. “Individuals with relatively high social class are more overconfident,” they concluded. And, they said, others buy into it. The result? “Advantages beget advantages.”

It’s difficult not to be impressed by a colleague with, say, an Ivy League education, tailor-made suit and a spring in their step. “Social class shapes the beliefs that people hold about their abilities and that, in turn, has important implications for how status hierarchies perpetuate,” the lead authors, Peter Belmi, assistant professor of leadership and organizational behavior at the University of Virginia, and Margaret A. Neale, a professor of management at Stanford University, wrote.

They come to meetings with soft skills that are invaluable to climbing up the corporate ladder: They might have learned how to schmooze at an early age, and feel comfortable talking to senior management as if they’re old friends. They know how to affirm people’s ideas and make them feel good about themselves, and maybe even repackage a couple for themselves. But what if they’re better at throwing shapes than pitching ideas?

Impression management can, indeed, trump smarts, the research released Monday said. Other people often assume they’re more competent than they are, which perpetuates social inequality and confers a class advantage on those individuals, the researchers said, even if they’re less competent than co-workers from a working-class background. “It can provide them a path to social advantage by making them appear more competent in the eyes of others,” they added.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Class distinctions can also affect people’s careers

Their findings, “The Social Advantage of Miscalibrated Individuals: The Relationship Between Social Class and Overconfidence and Its Implications for Class-Based Inequality,” help explain why individuals who work at elite and prestigious firms tend to come from elite educational institutions, and why those born in the “upper-class echelons” are likely to remain there, the authors said. They say it’s a cycle that keeps privileged people at the top.

Belmi and Neale tested these ideas across four large studies with a combined sample of 152,661 individuals. In one mock job interview, they found that “higher-class individuals were more overconfident.” That overconfidence, in turn, made them appear more competent and more likely to attain social rank.” In other words, they were more likely to get the job.

People from working-class backgrounds in high-status occupations earn 17% less, on average, than individuals from privileged backgrounds.

A separate 2016 study, “The Class Pay Gap in Higher Professional and Managerial Occupations,” and published in the American Sociological Review, took advantage of newly released data from Britain’s Labour Force Survey, and examined the relative openness of different high-status occupations and the earnings of the upwardly mobile within them.

Those researchers from the London School of Economics found a distinction between traditional professions that typically recruited from the upper classes — such as law, medicine and finance — which are dominated by the children of higher managers and professionals, and more technical occupations — such as engineering and IT — that recruit more widely from all strata of society.

There’s a “class ceiling” for employees from working-class backgrounds, those researchers found. “Even when people who are from working-class backgrounds are successful in entering high-status occupations, they earn 17% less, on average, than individuals from privileged backgrounds. This class-origin pay gap translates to up to £7,350 ($11,000) lower annual earnings.”

Don’t miss: The ‘best job in America’ pays over $108,000 a year — and has a high number of job openings

Inequality around the world has reached a tipping point

Notably, ingratiating yourself with your boss, whether you come from a privileged background or not, can have negative consequences, according to Anthony Klotz, an associate professor of management in the College of Business at Oregon State University and the lead author of a study on impression management techniques that was published in the October 2018 edition of the peer-reviewed Journal of Applied Psychology.

Donald Trump said in 2017, ‘One thing we’ve learned. We have by far the highest IQ of any cabinet ever assembled.’

Klotz and his co-authors examined how 75 mid-level managers at a large publicly-traded company used two “impression management” techniques — ingratiation with the higher-ups and self-promotion — over two weeks. Those who flattered the boss appeared to have a false sense of security and were more likely to lack self-discipline. As a result, they were uncivil to co-workers, skipped meetings and surfed the internet rather than working.

President Trump is known for his remarkable self-confidence and ability to speak off-script in front of a crowd. He’s been asked about his own presidential ambitions since the 1980s. The president, who was born into a wealthy real-estate family, has said he doesn’t have time to read books. (On the first day of his inauguration celebrations in 2017, Donald Trump told reporters: “One thing we’ve learned. We have by far the highest IQ of any cabinet ever assembled.”)

Academia, which is often regarded as the great economic and social equalizer in modern society, is not immune from this kind of “class ceiling.” In “Presumed Incompetent,” a collection of personal essays on the intersection of race and class at universities, Samuel H. Smith wrote, “Universities have much in common with elite country clubs. The academic credentials are necessary to be invited to join, but like all country clubs, not all members are perceived as equal.”

In the U.S., out of 100 children whose parents are among the bottom 10% of income earners, only 20 to 30 of them actually go to college.

Still, such structural class systems help keep wealth in the hands of the few, economists say. The U.K.-based House of Commons Library said last year that, based on current trends, the richest 1% will control nearly 66% of world’s money by 2030. Based on 6% annual growth in wealth, they would hold assets worth $305 trillion, up from $140 trillion today, the Guardian reported.

There is an opportunity gap as well as a wealth gap, particularly when it comes to getting a college education. In the U.S., out of 100 children whose parents are among the bottom 10% of income earners, only 20 to 30 of them actually go to college. However, 90 out of 100 children go to college if their parents are within the top 10% earners.

Ultimately, the divergence in the levels of inequality has been “extreme” between Western Europe and the U.S., according to a separate report, released last year by the World Inequality Lab, a research project in over 70 countries based at the Paris School of Economics, and co-authored by the French economist Thomas Piketty. Put bluntly, he says the existing political, corporate and cultural structures help ensure that the rich get richer and the poor, well, like it or lump it. “The global middle class has been squeezed,” the report said.

In their researcher, Belmi and Neale say many scholars have suggested that social inequalities persist because of systemic prejudice that make it difficult for those at the bottom to improve their standing. They say mainstream institutions should recognize the value and social norms of under-represented groups. “Structural inequalities may be hard to dismantle,” they write, “because those who wield the most influence are motivated to preserve their advantages.”

Get a daily roundup of the top reads in personal finance delivered to your inbox. Subscribe to MarketWatch’s free Personal Finance Daily newsletter. Sign up here.