ATLANTA (Project Syndicate) — Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe prioritized pomp over policy while hosting President Donald Trump this week.

The one exception was the issue of North Korea, which recently conducted more short-range missile tests off its east coast. Abe is clearly anxious about keeping Japan and the United States on the same page now that Trump’s denuclearization talks with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un have faltered.

But at a joint press conference on Monday, Trump dismissed concerns about the latest tests — breaking not just with Abe, but also with his own advisers.

North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un is quietly building a new united front with China and Russia, much to the detriment of U.S. interests in the region.

Abe has every reason to worry that Kim is gaining an important diplomatic edge. To be sure, as the North Korean economy struggles and food shortages loom, Kim’s bromance with Trump has failed to secure an easing of economic sanctions. But he has now reshuffled his negotiating team and tried to strike a statesmanlike pose, offering to hold yet another summit with Trump if the terms are right.

At the same time, Kim has been shoring up his position for further negotiations, not least by reaching out to China and Russia. Such overtures by the North Korean regime certainly are not unprecedented, but they are unusual.

As the scion of a dynasty that has jealously guarded the North’s independence for 70 years, Kim, like his grandfather, Kim Il-sung, the state’s founder, regards national self-reliance as sacrosanct. Though China and Russia are the Kim regime’s traditional allies, Kim’s grandfather and his father, Kim Jong-il, always kept their distance from the two powers, often playing one off against the other.

By contrast, Kim is teaming up with both to tilt the geostrategic field in his favor.

China, Russia, and North Korea most likely are not sharing a script, but they do appear to have settled on a division of labor, and are operating accordingly.

Kim is doing his job on the Korean Peninsula, exploiting South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s eagerness for rapprochement in order to drive a wedge between South Korea and the U.S. He is even entertaining the possibility of talks with Abe, who is desperate not to be excluded from the high-level exchanges.

China, meanwhile, is playing its traditional role as the North’s most influential partner. Ignoring U.S. demands that Kim must abandon his nuclear program before sanctions can be eased, China has suggested that sanctions relief could be used as a confidence-building measure on the way to a political resolution.

For its part, Russia, which participated in failed negotiations to end North Korea’s nuclear program more than a decade ago, has now taken the field on Kim’s behalf.

Last month, Kim and Russian President Vladimir Putin met for the first time. Rejecting the idea that U.S. and South Korean security guarantees could ever suffice to persuade Kim to follow through with denuclearization, Putin called for renewed talks with Russia and China at the table.

This Sino-Russian-North Korean collaboration will most likely continue.

Kim has already made a habit of calling Chinese President Xi Jinping before and after his summits with Trump, and his regime will probably be in more frequent contact with the Kremlin, too.

This does not bode well for U.S. objectives on the Korean Peninsula. Though Russia and China will pay lip service to the need for denuclearization, neither country has ever seriously tried to impede the Kim regime’s weapons program.

The willingness of China and Russia to tolerate a nuclear-armed North Korea reflects a strategic calculation.

Even if they are often unhappy with Kim’s behavior, their top priority is to shore up his regime. Were it to collapse, the likely outcome would be a reunited Korea under the government in Seoul; China and Russia would suddenly have a U.S. ally — and potentially even U.S. forces — on their borders.

Given the stakes, neither country is likely to curb its sanctions-busting oil shipments or, in China’s case, rising cross-border trade.

Moreover, China and Russia have plenty to gain from playing a more active role in the Korean nuclear issue. The Kim regime wants U.S. military forces removed not just from the Korean Peninsula, but from the entire Western Pacific theater. That would suit China and Russia just fine.

In the meantime, the added attention on U.S. forces in Asia provides useful political fodder at home, especially now that Trump has withdrawn the U.S. from the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with Russia. Both Russia and China are concerned about the U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-missile system that is now operational in South Korea.

But Sino-Russian cooperation isn’t just about the Korean Peninsula.

As Western sanctions in response to Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea have begun to bite, China has become an increasingly important market and source of investment for Russia. And now that China is supplanting America’s role in Asia, Russia has all the more reason to improve its relations with the new power.

At the same time, it is deepening its economic ties across the region, with plans to triple bilateral trade with Vietnam by 2020.

For China, Russia offers not just energy and raw materials, but, more important, a potential military partnership. Russia can provide defense technologies and the benefits of joint training; and if a conflict arises, it could be China’s main ally in Asia.

Given Trump’s history of threatening, on Twitter, to launch a nuclear war against North Korea, it would be surprising if Russian and Chinese military strategies did not already feature contingency plans for the Korean Peninsula.

Whether Kim’s approach will pay off at the negotiating table remains to be seen.

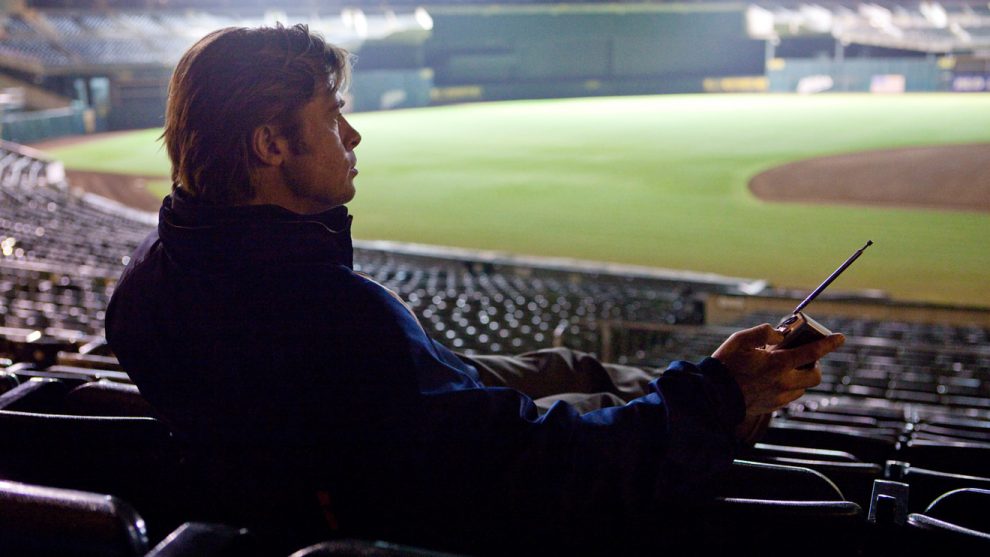

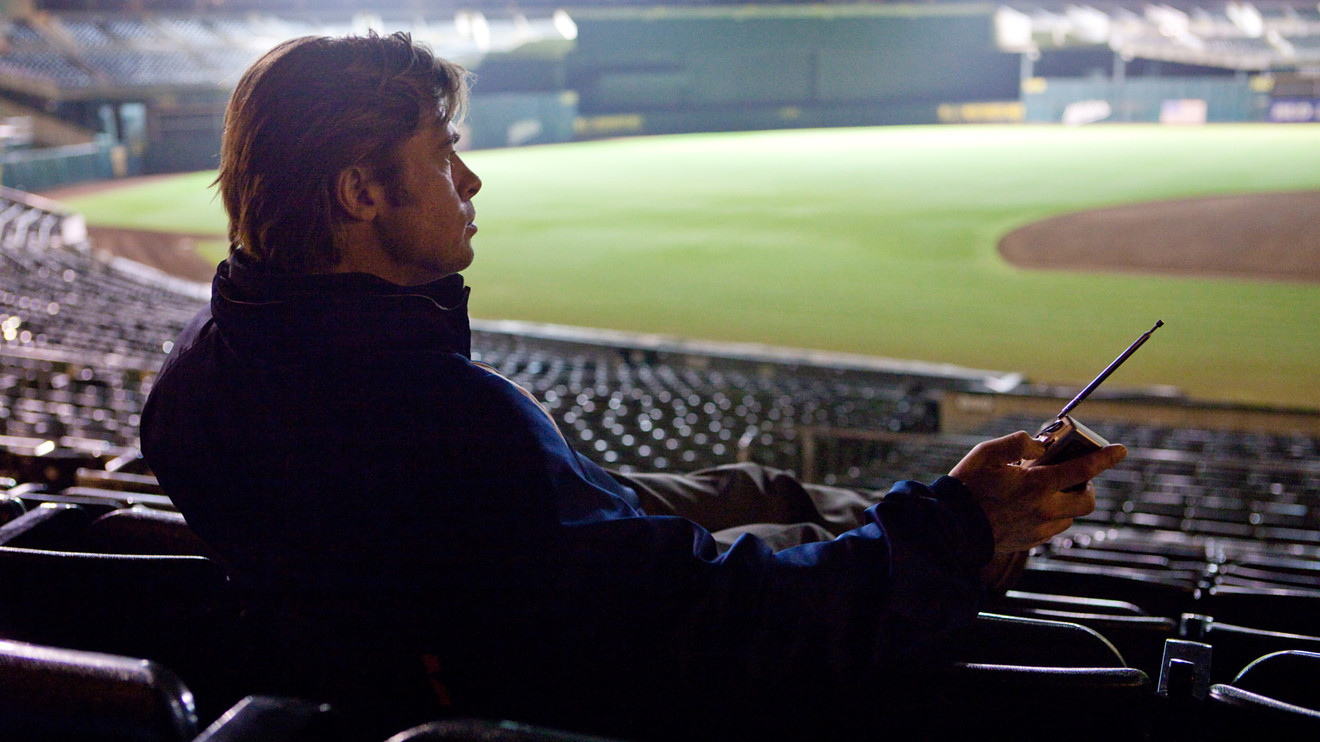

But any sports fan should recognize his game plan and the debt he owes to Billy Beane, the general manager of the Oakland Athletics. In 2002, Beane led the A’s to the longest winning streak in Major League Baseball history, not by using sluggers who occasionally blasted homeruns, but by hiring consistent base-hitters.

Despite striking out at the nuclear summits in Singapore and Hanoi, Trump continues to boast that has already knocked the ball over the fence. Meanwhile, Kim is fielding a team that can chalk up consistent points for him over the long term.

Kent Harrington, a former senior CIA analyst, served as national intelligence officer for East Asia, chief of station in Asia, and the CIA’s director of public affairs.

This article was published with permission of Project Syndicate — Kim Jong Un’s Moneyball Strategy.