A majority of California ride-hailing drivers are minorities and immigrants. The Proposition 22 campaign backed by Uber, Lyft and other gig companies reflect that, but the issue is complicated for Black and brown workers.

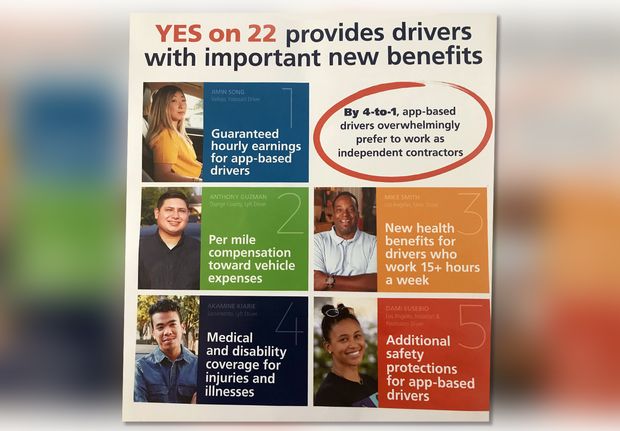

Campaign mailer

As Election Day nears, California voters are being bombarded with ads featuring smiling Black and brown faces championing Proposition 22, the initiative by Uber Technologies Inc., Lyft Inc. and other gig companies that seeks to exempt them from a state law requiring them to treat drivers and delivery workers as employees.

Outside Uber’s UBER, +1.48% headquarters in San Francisco on Thursday, however, hundreds of Black and brown workers from throughout the state converged for a No on 22 protest, with drivers being joined by other union members, such as janitors, nurses and teachers, as well as elected officials. They want gig companies to stop exploiting workers, and from using the initiative to lock in “a caste system that will have recourse for generations to come,” said Cherri Murphy, a Lyft driver and Gig Workers Rising organizer, as she addressed other protesters.

A majority of gig workers in California are minorities and immigrants, studies and the gig companies themselves say, and the companies have spent a record amount — more than $190 million — supporting the proposition and publicizing the support of different groups in the Golden State, including civil-rights organizations. Many of the people featured in the mailers and TV ads have been paid anywhere from $500 to a couple of thousand dollars by the “yes” side, which has also paid modeling and casting agencies, according to state records.

More on Prop 22: How Uber and Lyft’s business model could be changed on Election Day

The Yes on 22 website includes a list of 34 “community advocate” groups that support the measure, but it is unclear exactly how gig companies garnered that support, and the extent of it. The most prominent example is the NAACP, with the statewide group and several local chapters named in the list.

The head of the state NAACP, Alice Huffman, was featured in an Uber email campaign to its users titled “Why communities of color support Prop. 22.” But CalMatters reported that Huffman owns a consulting business that was paid more than $1 million by different campaigns, including Prop. 22, this year. The state NAACP has not returned a request for comment.

In the Yes on 22 campaign’s expenditures reported to the California Secretary of State, payments to Huffman’s consulting firm, AC Public Affairs, were identified as payments to “campaign consultants.” The campaign has disclosed $3.97 million in payments to more than two dozen campaign consultants, roughly a fourth of what their opponents have spent in total but less than 3% of the money that the Yes on 22 campaign has collected.

George Holland, president of the Oakland, Calif., branch of the NAACP, told MarketWatch the measure has raised a dilemma for his local chapter, which has chosen to stay neutral on the proposition.

“Some people just want to have temporary employment, but some are working full time,” he said. “It’s very difficult to take a side. We’re damned if we do, damned if we don’t.”

Uber driver Karim Benkanoun holds up a sign urging a no vote on Proposition 22 in Oakland, Calif. on Oct. 9, 2020. Ahead of a referendum that could upend the gig economy, he said his relationship with the ride-hailing giant must stop being a one-way street. “If you’re a driver with Uber or Lyft, you’re nothing,” Benkanoun said. A majority of gig workers in California are minorities and immigrants.

AFP via Getty Images

Opponents not only decry the initiative — any amendments to which would require a seven-eighths majority in both houses of the state Legislature — they also call out the gig companies’ campaign tactics, which have included antiracism Uber billboards and paying for the proposition to appear in “progressive” mailers — saying the minorities and immigrants who comprise the bulk of the gig companies’ workforces are being denied minimum wage, health benefits and other protections to which employees are entitled.

See: Protesters call Uber’s antiracism billboards ‘hypocritical and offensive’

The gig companies’ campaign is “a wolf disguised in sheep’s clothing,” said Shamann Walton, a member of San Francisco’s board of supervisors, during a virtual press conference organized by the No on 22 campaign last week. “It is infuriating hypocrisy. They claim to be an equity campaign. We know what it will do is undermine [the racial equity] we’ve been fighting for.”

The Yes on 22 campaign lists a few dozen supporters it calls “community advocates,” and uses the names of those groups prominently in its many mailers to California residents. But one of those groups, Black Lives Matter Sacramento, was taken off the list after MarketWatch brought to the campaign’s attention that its leader, Tanya Faison, said she was an individual supporter of the initiative but that the rest of the group was not. A spokesman for the campaign said the inclusion of the group was due to a miscommunication with Faison. When reached by MarketWatch, Faison said she had no comment about her support for the initiative.

Nearly a couple of dozen community advocacy groups on the list have not returned requests for comment. And at least a handful of other organizations have been impossible to contact: one appears to be defunct; one does not have any online presence or listing; another seemed to exist only as a Facebook FB, -1.70% group. The Yes on 22 campaign has provided contact information for a couple of these groups, but they have not responded to requests for comment.

Some advocacy-group leaders say they support the initiative because their communities need the gig economy for extra income — or any income — especially during the coronavirus crisis, or to serve neighborhoods that have traditionally been underserved.

“I live in a neighborhood where taxi cabs don’t come but Uber and Lyft LYFT, -3.52% show up,” said the Rev. K.W. Tulloss, president of the Baptist Ministers Conference of Los Angeles and Southern California, who said he couldn’t recall exactly how he was asked to support the measure. He added that he has also driven for Uber in the past few years to help supplement his income, so “I stand with the drivers who desire to have autonomy and be independent contractors.”

Likewise, Bay Area-based Black Women Organized for Political Action said in a statement that “Our PAC board deliberated on this position and ultimately surveyed our membership and drivers within our circle of family, friends and colleagues who happened to be largely African-American. Most felt strongly that they wanted to remain as independent contractors/freelancers with this freedom to work when they choose to do so.”

Cassandra Jennings, president of the Greater Sacramento Urban League who said she volunteered to support the campaign after “talking to a couple of people in the industry,” echoed that sentiment.

“The gig economy is for people who don’t want to work 9 to 5 and want to do things differently,” Jennings said. “Drivers tell me they’re happy with what they’re making, that they’re making it work doing it part-time.”

As for the drivers working full-time, “they shouldn’t be exploited,” she said. “The question is: How do you provide an opportunity for both to exist?”

The companies tout schedule flexibility as their main selling point, and warn that hundreds of thousands of people in the state could lose their ability to make money if they must be considered employees instead of independent contractors. Over the summer, Uber and Lyft even threatened to leave California when a judge ordered them to immediately comply with state law and classify their drivers as employees.

See: Uber and Lyft granted emergency stay, shutdown averted in California

“Uber and Lyft leaving California would hurt us more,” Tulloss said.

Labor experts and others say nothing is stopping the gig companies from hiring their drivers and couriers as employees, and giving them the choice to work full- or part-time, in shifts. In fact, such an example exists among the app-based platforms: Instacart has a hybrid workforce, with both workers it considers employees and independent contractors.

“There is no reason why these companies cannot treat their workers as employees,” said William Gould, professor emeritus at Stanford Law School and a former chairman of the National Labor Relations Board. “And, if they get away with this, other companies will be induced to expand the ranks of this underclass.”

In an interview with MarketWatch before last week’s protest, Murphy (who paused driving for Lyft in April because of the pandemic) said the companies “paint misclassification and exploitation as if it’s the best thing for Black and brown workers. They’re not going to talk about letting drivers fend for themselves when the pandemic first hit.”

Meanwhile, the drivers who took part in a caravan from Southern California last week before gathering at the protest in San Francisco, as well as their supporters, were clear about where they stand.

Carlos Ramos, a Lyft driver from Bakersfield, slammed the gig companies’ tactics and the money they have spent: “They can’t take our democratic process and pervert it,” he said.

Jennifer Esteen, a registered nurse for the city of San Francisco and vice president of organizing at SEIU Local 1021, compared today’s gig-worker battle to farmworkers standing up to big agriculture in the 1960s.

“Workers move this country,” she said. “Workers make everything possible… If Prop. 22 passes, all [workers] are at risk.”

See also: The pandemic turned Postmates’ IPO plans into a bidding war between Uber and Wall Street

Asked for comment about Thursday’s protest, a spokesman for the proposition’s campaign said, “By passing Prop. 22, California voters can protect the app-based jobs that hundreds of thousands of Californians depend on to earn supplemental income and the services that millions of California families rely on for safe, affordable, and reliable transportation and delivery, now more than ever during the pandemic.”

Prop. 22, which appears to be the most expensive California ballot initiative ever, is backed by more than $190 million from Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart and Postmates, according to the most recent state records. By contrast, labor unions and other organizations funding the opposition have poured about $16 million into their campaign.

Reporter Elisabeth Buchwald contributed to this article.