‘Tis the season for year-ahead forecasts, and that means you should run, not walk, the other way.

To quote Warren Buffett: “The only value of stock forecasters is to make fortunetellers look good.”

I was reminded of Buffett’s wisdom after spending several hours reviewing the year-ahead forecasts made one year ago, in December 2021. It was a sobering experience. I was struck not only by how wrong many of those forecasts were, but also by the confidence with which they were presented.

Take Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has been one of the most consequential developments of the year, both for the financial markets in particular and geopolitically as well. In December of last year, even though Russia had already amassed tens of thousands of troops on the Ukrainian border, only a precious few of the Wall Street forecasts I had received in my inbox even mentioned Ukraine. Even fewer believed Russia would actually invade. And even fewer still thought that, if Russia did invade, it wouldn’t be over almost immediately with Ukraine quickly being absorbed into Russia. No one imagined that a war would be continuing today.

Read: Volodymyr Zelensky and ‘the spirit of Ukraine’ named Time’s Person of the Year

You might think that this would lead to humility on the part of the forecasters. But that hasn’t happened. They’re back at it this year, confidently forecasting what will and won’t happen in 2023. Truly we can say about them that they’re often wrong but never in doubt.

You might excuse the forecasters for being so wrong on Ukraine, since foreign policy is not their expertise. But the track records of their financial and markets forecasts are not any better.

Here’s a quick review of a few of the more spectacular market forecast failures from a year ago. I have omitted any firm and analyst names, since the point of this column is not to call anyone out individually but to question the practice of making year-ahead forecasts in the first place.

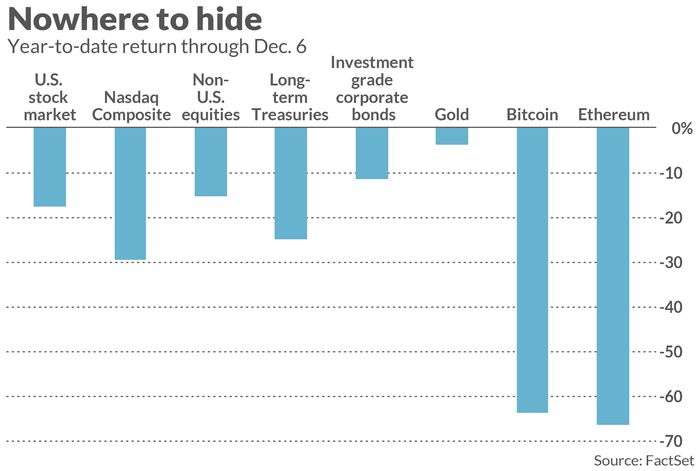

As you can see from the accompanying chart, 2022’s returns don’t paint a pretty picture.

- Stocks: I didn’t come across one Wall Street firm that had been bullish in 2020 and 2021 but which, in December of last year, forecast a bear market in 2022. (That doesn’t mean no firm did so; it just means I couldn’t find any such firm.) The firms that were forecasting a bear market in 2022 were bearish for some or all of the prior two years as well—so it’s difficult to credit them with “calling” the 2022 bear market. A prominent analyst from one of the largest brokerage firms forecast that 2022 would be a better year than 2021.

- Inflation: The persistence of inflation has been one of the biggest stories of the year, of course. And yet many prominent forecasters didn’t even come close to anticipating it, instead predicting that inflation would decline. One of this country’s largest investment firms predicted that Eurozone inflation would decline to below 2% by the end of this year. In fact it’s currently running at a 10% annual pace.

- Interest rates: Given how wrong many forecasters were when it came to predicting inflation, it perhaps is little surprise that many were also wrong when it came to interest rates. One prominent firm forecast that the Federal Reserve wouldn’t start hiking interest rates until 2023. Another firm predicted that the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield would end the year no higher than 2.5%. It currently stands at 3.4%.

- Cryptocurrencies: The year’s biggest losses were concentrated in cryptocurrencies, with bitcoin and Ethereum—the two biggest—each losing more than 60% year to date. But among those Wall Street firms making crypto forecasts, an “up” year was the most common prediction. Several forecast that bitcoin would hit $100,000 this year, compared to a price around $46,000 at the end of last year. It currently trades at around $17,000. Another firm predicted that Ethereum, which ended last year around $3,700, wouldn’t drop below $2,900. It currently trades at around $1,200.

The ‘I know’ versus the ‘I don’t know’ school

One of the best thought pieces about the perils of forecasting, entitled The Illusion of Knowledge, was penned a couple of months ago by Howard Marks, co-founder and co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management. He divided Wall Street analysts into two groups: Those in the “I know” camp and those in the “I don’t know” camp.

Marks writes: “It’s easy to identify members of the ‘I know’ school: They think knowledge of the future direction of economies, interest rates, markets and widely followed mainstream stocks is essential for investment success. They’re confident it can be achieved. They know they can do it… They’re also glad to share their views with others, even though correct forecasts should be of such great value that no one would give them away gratis. They rarely look back to rigorously assess their record as forecasters.”

In contrast, Marks continues, the adjective that best describes analysts in the “I don’t know” school is guarded. “Its adherents generally believe you can’t know the future; you don’t have to know the future; and the proper goal is to do the best possible job of investing in the absence of that knowledge.”

Marks argues that the intellectually honest thing for a forecaster is to be in the “I don’t know” camp. He quotes AmosTversky, the late Stanford behavioral economist: “It’s frightening to think that you might not know something, but more frightening to think that, by and large, the world is run by people who have faith that they know exactly what’s going on.”

Marks ended his thought piece with the following anecdote: “A few years ago, a highly respected sell-side economist with whom I became friendly during my early Citibank days called me with an important message: ‘You’ve changed my life,’ he said. ‘I’ve stopped making forecasts. Instead, I just tell people what’s going on today and what I see as the possible implications for the future. Life is so much better.’”

Bliss

Marks asks: “Can I help you reach the same state of bliss?”

For retirees and near-retirees, bliss manifests as a financial plan that outlines how to respond to the various possible outcomes. Rather than betting all or nothing on a particular forecast coming true, a good financial plan is built on the recognition that the future is profoundly uncertain.

Such a plan begins with making sure your basic needs will be met, come what may. That almost certainly means annuitizing a portion of your portfolio, thereby guaranteeing a steady stream of income. Only after you have that guaranteed income should you even contemplate making speculative bets in your portfolio.

Then, and only then, should you pay attention to what the forecasters are saying.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected]