The Federal Reserve has a chronic white male problem that is going to make it harder for the institution to help lead the country at a historic moment of crisis that, by definition, requires a strong diversity of views.

When Jay Powell addressed widespread recent protests and their likely economic effects at his recent press briefing, his comments felt stilted, belated and out of touch.

“I speak for my colleagues throughout the Federal Reserve System when I say that there is no place at the Federal Reserve for racism and there should be no place for it in our society,” Powell said.

“Everyone deserves the opportunity to participate fully in our society and in our economy.”

Also read: The pandemic is accelerating the racial wealth divide. Here’s how we turn it around.

That sounds nice, but it’s pro forma, and lacks the kind of empathy that a person who has truly struggled in life might have for others in a similar position.

The numbers don’t lie

Also: the Fed loves statistics — and the numbers, in this case, don’t lie. The Fed has a serious lack of diversity at its highest levels.

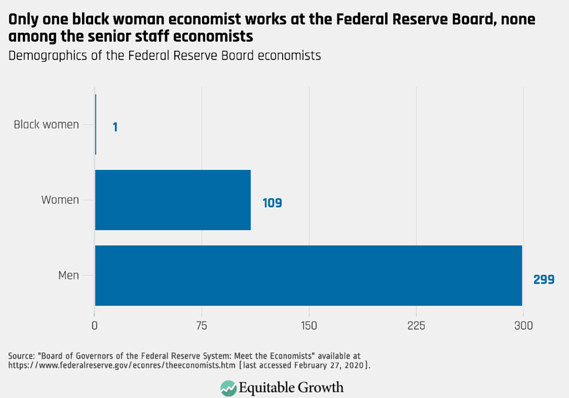

Among the 408 economists at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, only one is a Black woman, says ex-Fed economist Claudia Sahm, now at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

“Few other women of color or minority men work for the Federal Reserve Board,” she says. “Moreover, only a fraction of the staff’s research and economic analysis focus on race. People of any background could study race, yet in real life, our lived experiences often guide the questions we ask. Economists are no different.”

Sahm adds that “economists of color missing from the Fed means that race has largely been missing from its policy deliberations.

Only one Black woman is employed as an economist at the Fed..

Equitable Growth

Contrast Powell’s hollow words to those penned by his colleague Raphael Bostic. The president of the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank, Bostic is the only Black American who gets a direct say on U.S. monetary policy.

Lasting drag on the economy

Bostic warns that racist practices and polices—on top of their more obvious social and psychological toll—generate a lasting and pervasive drag on the economy as well.

“These events are yet another reminder that many of our fellow citizens endure the burden of unjust, exploitative, and abusive treatment by institutions in this country,” Bostic wrote about the deaths of Black Americans at the hands of police.

Bostic, appointed to the Atlanta Fed’s helm in 2017, is the first ever Black president of a regional Fed bank, while the Fed’s board has had only three Black governors. Janet Yellen was the first and only woman to ever head the central bank, which was founded in 1913. Donald Trump didn’t reappoint her to a second term.

The effects of COVID-19 have been disproportionate on Black Americans, from both the health and economic standpoints. Not only are infection and death rates orders of magnitude higher among Black individuals, so have the job losses incurred from the pandemic-related slump fallen most heavily on the Black community.

The Black jobless rate had already jumped sharply to 16.8% by May, compared with 12.4% for whites. The figure will likely move even higher before receding.

“The legacies of these institutions remain, and we continue to experience misguided bias and prejudices that stem from these stains on our history. These have manifested in the worst way possible—in the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Dana Martin, and, sadly, so many others,” Bostic wrote.

The problem for the Fed is that the absence of Black voices at the highest levels means that America’s flagrant racial problems are often ignored or misunderstood.

William Spriggs, the chief economist at the AFL-CIO, says this is an issue with the economics profession generally, since its models make assumptions about race that are, quite frankly, racist.

White privilege

Powell is a child of white privilege. He went to Georgetown Prep, then Princeton, then Georgetown Law. He was editor-in-chief of the Georgetown Law Journal, and also a legacy student—his maternal grandfather, James Hayden, was dean of the Columbus School of Law at Catholic University of America and later a lecturer at Georgetown Law School.

Importantly, while Powell spent some years in government before his 2012 appointment to the Fed’s board of governors, he made his career—and multimillion-dollar fortune—at the influential private-equity firm Carlyle Group.

Janet Yellen, the first and only woman to ever lead the powerful U.S. central bank for it is over 100-year history, tried her best to change things. But it’s hard to reverse a century of institutional racism and misogyny in just four years—Donald Trump ensured Yellen wouldn’t get a second term, instead appointing white man and financier Powell.

Over those 100-plus years, the Fed’s highly influential, Washington-based board has had just three Black governors, all of them male. The most recent was Roger Ferguson, who was vice chair for part of Alan Greenspan’s 18-year tenure.

Double standard

Narayana Kocherlakota, former president of the Minneapolis Fed, says the double standard applies to the Fed’s hiring practices, which he argues sets a higher bar for minorities.

“How does this exclusion happen? In every hiring or appointment, decision makers necessarily put weight on candidates’ ‘intangibles’—critical attributes, such as knowledge of how a person works with others, that are not directly reflected in their degrees or experience,” Kocherlakota says.

“The evidence suggests that, in the Fed’s case, the largely white decision makers are giving non-Black candidates more credit for such off-the-formal-record qualities. Simply including and relying upon more Black voices in the process could help correct this bias.”

To his credit, rather than ditching Yellen’s incipient effort at addressing longstanding problems with diversity, and an absence of Black voices in particular, Powell has continued to listen to communities and activists seeking greater equality.

During his June 10 press conference, Powell referred to the disproportionate rise in Black unemployment as “heartbreaking.”

“Unemployment has gone up more for Hispanics, more for African-Americans,” he said. “That’s really, really unfortunate, because if you just go back two months, where we had effectively the first tight labor market in a quarter-century—so, we really want to get it back.”