For Facebook, the conclusion of President Trump’s term in office meant a respite from the regular provocations of a leader who seemed intent on pushing the limits of what social media companies would allow.

It also brought one final dilemma: whether to reinstate his account, locked down indefinitely in the aftermath of the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, or shut it down for good.

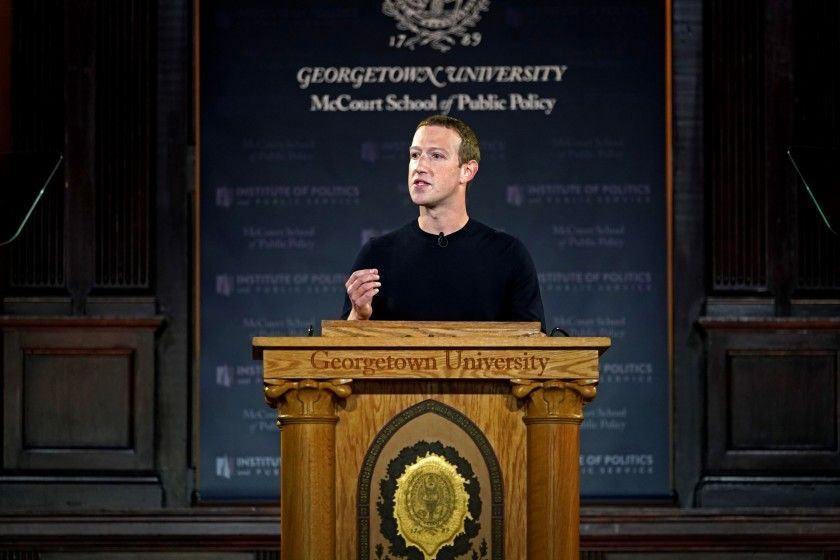

But Facebook didn’t decide. Instead, the company punted the question to a third-party organization convened last year explicitly to take such thorny questions off Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg’s shoulders.

“Facebook is referring its decision to indefinitely suspend former U.S. President Donald Trump’s access to his Facebook and Instagram accounts to the independent Oversight Board,” the company announced. “We believe our decision was necessary and right. Given its significance, we think it is important for the board to review it and reach an independent judgment on whether it should be upheld.”

In a separate statement, the Oversight Board said that a five-member panel would review the case and make a recommendation to the entire board about whether to uphold or overturn the ban. Facebook has committed to implementing whatever the majority ends up choosing.

Over the last few years — as the question of what internet platforms should do about disinformation, hate speech and harassment has become a topic of national discussion — industry and political leaders have settled into a familiar routine. Politicians demand the tech platforms do a better job balancing free speech and public safety; tech executives invite politicians to put their demands into the form of new regulations they can try to follow. Neither side has shown much inclination to commit to anything that could involve political blowback or unforeseen consequences.

For Zuckerberg, referring the Trump ban to the Oversight Board represents a way out of this impasse — and a tactic other companies are likely to copy, if only for want of better options.

“It’s just like trying to offload the responsibility and say, ‘Oh, we’re doing our best and this is somebody else’s problem now,’” said Tracy Chou, founder and CEO of anti-harassment software company Block Party.

The Oversight Board aims to serve as a Supreme Court to Facebook’s nation-state. Its funding and structure are independent of Facebook proper, and it’s tasked with ruling on specific moderation decisions the platform makes — whether a controversial post was rightly deleted, for instance, or whether a certain ex-president should stay banned.

“We as a society have to decide who we want to be making these sorts of determinations,” said Talia Stroud, a University of Texas at Austin professor and co-founder of digital media research group Civic Signals, in an email. “Do we want the choices to be in the hands of government? In the hands of a company? External oversight?”

The Oversight Board falls under that third category — but “external” is a relative term.

Facebook played a role in selecting the initial crop of board members (which includes academics, political advocates, journalists and lawyers from around the world), but it can’t remove them and won’t get to hire new ones in the future. It’s also unclear how wide an effect the board’s rulings will have. The board says it plans to rule on “highly emblematic cases,” enabling it to develop a body of precedent that could guide future moderation questions. But while the board issues binding decisions on specific cases it hears, it can only make recommendations about Facebook policy more generally.

“The entity cannot demand to review particular decisions about Facebook’s operations, nor can it compel Facebook to modify its rules or to accept any recommendations for new policies,” said Sharon Bradford Franklin, policy director of New America’s Open Technology Institute, via email.

In the case of the Trump ban, Facebook has requested recommendations for how to handle future suspensions of political leaders, suggesting that wherever Trump winds up, other world leaders will likely follow.

Not everyone is happy with the way Facebook is delegating responsibility.

“We are concerned that Facebook is using its Oversight Board as a fig leaf to cover its lack of open, transparent, coherent moderation policies, its continued failure to act against inciters of hate and violence and the tsunami of mis- and disinformation that continues to flood its platform,” said The Real Facebook Oversight Board, a nonprofit project whose aim is to keep the company accountable through external pressure.

The Trump case “underlines the urgent necessity for democratic regulation,” the group added in its statement.

Also calling for democratic regulation is Facebook itself. In the statement announcing that the Oversight Board would review Trump’s case, vice president of global affairs Nick Clegg said “it would be better if these decisions were made according to frameworks agreed by democratically accountable lawmakers. But in the absence of such laws, there are decisions that we cannot duck.”

It’s a familiar refrain from company leadership. Over the last year or so, Zuckerberg has started calling for more active government regulation of social media, deeming it “better for everyone, including us, over the long term.” At a congressional hearing in October, he said Congress should update Section 230, the small chunk of legislation that gives websites flexibility to choose if and when they’ll censor users, “to make sure that it’s working as intended.”

But with politicians divided over whether the law should require platforms to do more moderation or bar them from doing any at all, prospects for a government-based solution remain dim in the short term.

The Oversight Board’s third-party model offers an out.

“So far, the Facebook Oversight Board is the only fully developed independent institution tasked with doing review,” said Noah Feldman, a Harvard law professor who initially came up with the idea for it, then persuaded Facebook to make it a reality. “I hope that if it performs well … other industry actors, and maybe eventually people in other industries, will follow suit.”

Meanwhile, some European countries where “the governments themselves don’t actually want to do all the work of content moderation” are already adopting regulations that require companies to have third-party oversight, he added.

But without the force of law behind it, that model also has its limits.

“They want to be able to say, ‘Look, we banned Trump, and our independent body agreed,’” said Mark Coatney, a former Tumblr employee who’s now working on a third-party social media moderation tool. “But if they did something that they thought the Oversight Board would not agree with, I don’t know that they would be sending it to the Oversight Board.”

(The Trump ban was submitted for consideration by Facebook. Although individuals can submit their own appeals to the board, they have to have an active, non-disabled account to do so — meaning Trump might not have been able to appeal his own ban if Facebook didn’t.)

While a third-party referee may solve the hot-potato problem for tech executives and politicians, it still leaves a small number of individuals making judgments that affect the rights of millions. To some, including Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, the ultimate answer must be to let social media users themselves decide what’s acceptable.

Dorsey has been pushing for an open-source “decentralized standard for social media” that’s “not owned by any single private corporation.” In his vision, internet users would be able to choose between dozens or hundreds of competing algorithms for curating tweets and other public content.

But Dorsey has said this effort will take “many years,” and it would require social media companies to voluntarily remove the barriers around their digital walled gardens. Until then, social media CEOs will have to choose between making unpopular content decisions or letting someone else do it for them.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.