(Bloomberg Opinion) — The New York Times recently released a dramatic infographic showing how much less progressive U.S. tax system have become since 1950. When the animation starts, most taxpayers are paying about 20% of their income in taxes, but the top 1% is paying almost 30%, while the country’s 400 highest earners are paying 70%. During the next 68 years, most brackets see their tax rate rise, while the richest 400 see their rate fall relentlessly. When the animation finishes, the top 400 individuals are paying just over 20% – lower than any other bracket.

These numbers are astounding, and they suggest that higher tax rates on the country’s wealthiest individuals are in order. But first, it’s important to understand what it does and doesn’t show.

First of all, the graph zooms in on the top brackets – it shows the tax rate at the 90th income percentile, then the 99th, then the 99.99th, and finally the top 400 people. If it had stopped at the 99th percentile, it would have shown roughly constant top tax rates over time; what looks like a dramatic fall in tax progressivity comes entirely from the tiny sliver of earners at the very top of the income scale.

Second, the graph doesn’t include transfers – the money that the government pays out. Overall, these have risen. This, along with rising taxes for the upper-middle class, is the main reason why the U.S. fiscal system as a whole has become steadily more progressive since 1950. Most of the country simply isn’t affected very much by what the government does to the 400 highest earners.

A final caveat is that the tax rate of top earners is very hard to measure because they earn their income in non-standard ways, and they try very hard to hide it from the tax collectors.

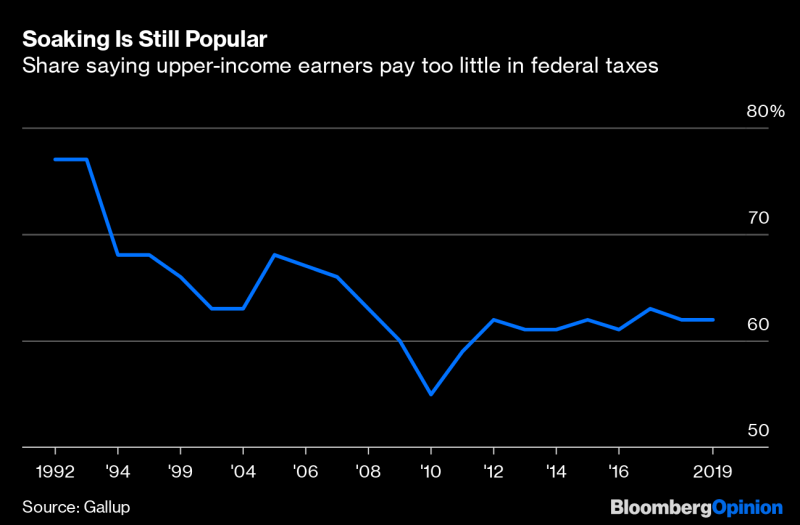

But despite all these caveats, it’s clear that tax rates for the richest handful of Americans have gone down a lot since the mid-20th century. And the country is starting to feel increasingly uncomfortable about that fact. The share of Americans who believe that high earners pay too little in taxes has come down a bit over the years, but it’s still a substantial majority:

Meanwhile, a number of the country’s wealthiest people, including Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, have called for their own taxes to be raised. Presidential candidate and billionaire Tom Steyer has echoed the call. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg has gone even farther, declaring that “no one deserves” the amount of wealth that he and other billionaires have accumulated.

So how can top earners be taxed? The first order of business is to raise the capital-gains tax rate. Despite news headlines about overpaid chief executives, the very top earners make most of their income from the financial assets they own. Taxing capital gains is unlikely to hurt business investment, given that the country is awash in savings earning increasingly low returns. Economic research has shown that cuts in dividend tax rates (which work similarly to capital-gains taxes) haven’t boosted growth or investment, so it stands to reason that raising rates wouldn’t hurt.

A second step is to repeal President Donald Trump’s new deduction for pass-through business income. This lets many top earners pay lower taxes by passing their income through an S corporation or other closely held company; it’s an important reason tax rates on the wealthiest are falling.

A third step is to create more tax brackets. The reason that top income tax rates were so high in the mid-20th century is because there were special brackets for very high earners. In 1920 there were more than 50 federal income-tax brackets, with the rate on income of over $1 million – about $12.8 million in today’s dollars – set at 73%. As of 2019 there are only seven brackets, with the top bracket set at just $500,000. Adding more brackets at the top of the income scale would allow steeper rates to be targeted at very high earners.

Taxing the highest earners has a number of benefits. It will raise some government revenue (though perhaps less than most ardent proponents expect). Higher income taxes may prompt wealthy people to shelter their money within corporations as they did in the 1950s, which could raise the declining rate of business investment.

And finally, taxing the rich more will increase social cohesion. Obligating the top earners to pay more creates a sense that American society isn’t just every man for himself, but that the most successful are required to give something back to the country that gave the opportunity to succeed. Buffett, Gates, Zuckerberg, Steyer and other extremely wealthy individuals seem to share the general yearning for a society that isn’t so divided into winners and everybody else.

(Corrects to indicate that taxes paid by the 400 wealthiest Americans are all taxes, not just federal taxes.)

To contact the author of this story: Noah Smith at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”61″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.

Add Comment