(Bloomberg) — If Chase Coleman didn’t exist, Hollywood would surely invent him.

Born into New York aristocracy and educated at fine schools, Charles Payson “Chase” Coleman III was all of 25 when the hedge fund legend Julian Robertson handed him $25 million to start his own fund.

At 29, he married a chemicals heiress who’d been featured in the documentary “Born Rich.” A gifted athlete, he’s been known to catch a few waves in the morning near his $19 million Hamptons home before helicoptering to his Manhattan office. He’s surfed with world champion Kelly Slater, invested with Snoop Dogg in a cannabis company and he’s almost a scratch golfer.

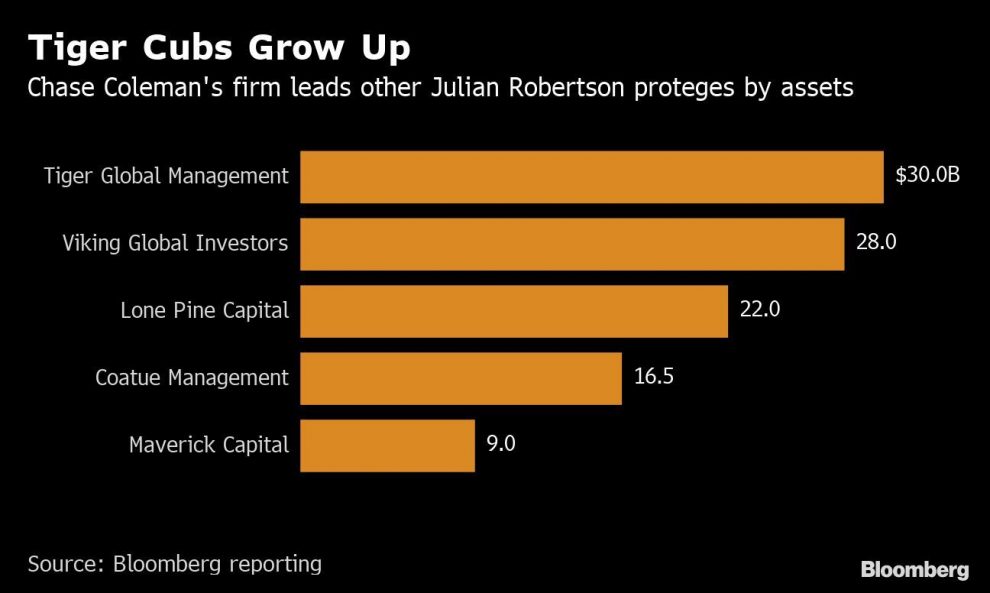

Today, at 44, Coleman sits astride a $30 billion behemoth, Tiger Global Management. Bets on public and private technology companies have helped him amass a $4.6 billion fortune and made him the youngest financier among the world’s 500 richest people, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

It’s hard to criticize a hedge fund up 25.5% in the first five months of this year, or a private equity unit that made $5 billion on a single investment. Not everything’s perfect, though, of course. For one thing, the firm may actually have too much money—something Coleman himself addressed recently.

“It’s not easy to manage a big pool of capital, and I’m challenged every day,” Coleman said last week at a Morgan Stanley conference, according to people who attended the event. You have to be deliberate in how you do it, he added, which is why he spreads his investments across public and private markets.

While assets have climbed, key personnel have departed, often to run their own money. Feroz Dewan, who ran public equities, left in 2015, as did Caleb Watts, Andrew Bellas and Alexander Captain. Lee Fixel, responsible for the firm’s push into India and behind some of its most lucrative investments, is exiting this month after 13 years.

And then there are the bubble-territory valuations.

“Tons of capital has gone into the technology space, and that could potentially reduce returns,” said Mark Buntz, chief financial officer of the William K. Warren Foundation, which has invested in Tiger Global’s private investment funds for more than a decade. “But I expect that Tiger Global will exercise the same discipline it has in the past, and won’t just go out and chase deals.”

Like Buntz, the majority of endowments and foundations that have entrusted money to Coleman are convinced he can navigate this. After all, he manages almost 50% more than his mentor Robertson ever did. He’s done it mostly with old-school stock picking and a staff of about 20 other investment professionals. His record of 20% annualized returns for his hedge fund—with only two down years—and 25% for private equity funds beats most peers.

Coleman, who associates describe as reserved and a quintessential WASP, declined to comment for this article.

He rarely speaks at public events and is seldom photographed. But he has been known to let his old-money guard down and get crazy. In 2016, Chase and his wife Stephanie bought a $52 million Central Park co-op. Last year, the couple hosted an after-party to the Save Venice masquerade ball where guests, including Paris Hilton, were welcome to vandalize the soon-to-be renovated apartment, the New York Post’s Page Six reported.

It was a moment of unwanted publicity for Coleman, who grew up on the north shore of Long Island, the son of a lawyer and an interior designer. A descendant of Peter Stuyvesant, he attended Deerfield Academy, the elite boarding school in Massachusetts, and went on to co-captain the lacrosse team at Williams College.

“I’ve known Chase since he was a young boy on Long Island and a good friend of my son Spencer,” Robertson said. So it was natural that his first hedge fund job was at Tiger Management.

Coleman worked as a technology analyst at Tiger for less than four years before getting a check from Robertson. In 2001, he became an official Tiger Cub, the term for Robertson proteges who started their own firms, a group that also includes Lee Ainslie and Andreas Halvorsen.

Originally Tiger Technology, the firm expanded to payments, education and other sectors and changed its name to Tiger Global. In the early 2000s, Coleman and partner Scott Shleifer added private investments to the mix, realizing before many of their peers that they might find higher returns outside of public markets.

During the 2008 financial crisis, Coleman’s hedge fund lost 26%, followed by a paltry 1% gain the next year. The young investor regrouped, vowing to return to his tech roots and avoid industries where politics or macro events could interfere.

Investors say his success comes from concentrated bets, pressing winners and quickly cutting losers—skills he learned from Robertson. He told the Morgan Stanley crowd that the person who does best is the one with the panic button farthest from his keyboard.

Other lessons he absorbed: Talent trumps experience, and hiring young people who can be coached produces the best money managers. The average age at Tiger Global is 32. The firm’s holiday cards could be mistaken for a class hiking trip photo, except that everyone is wearing matching high-end parkas, pants, boots and backpacks.

The coveted deal flow in China was helped by a young Tiger Global analyst charming corporate executives by bringing her baby to board meetings.

Among its biggest wins in China were Ctrip.com International Ltd. and JD.com Inc., investments led by Shleifer. What started out as a $200 million bet on JD.com in 2009 produced a $5 billion net profit.

The firm has also prospered in India. In 2009, Fixel led an investment in Flipkart, an e-commerce firm that helped change that country’s internet retail industry. It paid off last year when Walmart Inc. bought a majority stake, producing about $3 billion in profit. In all, Tiger Global’s venture unit has made more than 250 investments in 30 countries.

As assets have grown, Tiger Global has concentrated its bets. Seven equities, including JD.com, Microsoft Corp., Facebook Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., made up more than half of its long U.S. stock holdings as of March 31, according to regulatory filings. The firm held more than $1 billion worth of each stock at the time.

It’s still bullish on China, where companies are outspending on research and development. In the past, the firm has looked for businesses abroad that mimicked U.S. success stories. Now, it’s eyeing a profitable Chinese trend—food delivery—that it expects will expand in the U.S.

“Chase is great at analyzing companies and new technologies that are going to be at the forefront of the next growth cycle,” said Tim Ng, investment chief at Clearbrook Global Advisors. “He sees where the new opportunities are and how disruptive ventures can be.”

The wagers haven’t been without controversy. Last year, Tiger Global invested in Juul Labs Inc., the e-cigarette brand that has been blamed for stoking a youth health epidemic. The firm earned a $1.6 billion cash dividend a few months later when tobacco giant Altria Group Inc. bought 35% of the company. Since then, at least one foundation client said its board is “ actively discussing” the Juul holding.

Tiger Global raised $3.75 billion last year for its latest private vehicle, its 11th and largest ever, and at least one investor said he stayed away, fearing it had gotten too big. Even so, the 10th fund has been its most successful, returning an annualized 74%.

“I’ve watched his steady development over the years, first at Tiger and then on his own, with great pride,” Robertson said. “I am not surprised at all that he has become one of the brightest lights in the hedge fund business.”

—With assistance from Tom Maloney

(Updates with equity holdings in 23rd paragraph)

–With assistance from Pierre Paulden.

To contact the authors of this story: Hema Parmar in New York at [email protected] Karsh in New York at [email protected] Alexander in New York at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Katherine Burton at [email protected], Peter EichenbaumDavid Gillen

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com” data-reactid=”86″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.