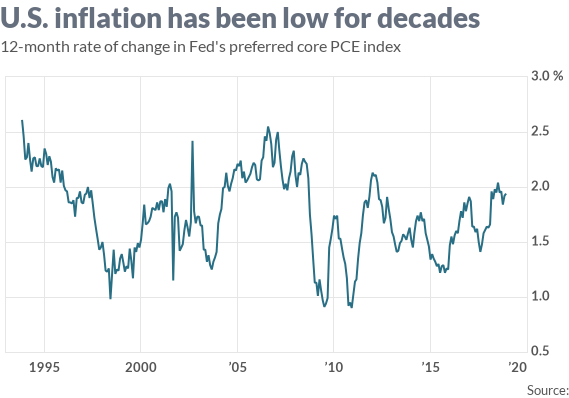

News flash: Inflation in the U.S. has been very low — unusually low — for a long, long time.

How long? Try a quarter of a century. That’s the last time inflation consistently ran above 3% a year.

Stubbornly low inflation is the chief reason the Federal Reserve has backed off plans to keep raising a key interest rate that influences the cost of borrowing for businesses and consumers. And it’s why Chairman Jerome Powell and other senior Fed officials are reexamining old assumptions about how inflation behaves after years of trying and failing to raise prices above what it considers a danger zone for the economy.

Read: Fed jettisons plans to lift interest rates in 2019. Here’s why

“We are almost 10 years deep into this expansion and inflation is still not clearly meeting our target,” Powell said last month. “That’s one of the reasons we are being patient.”

Future of inflation

The thorniest problem for the Fed is figuring out the future path of inflation.

Despite the lowest unemployment rate since the late 1960s and the fastest increase in wages in a decade, the rate of inflation actually fell slightly in the second half of 2018. Conventional wisdom says that’s not suppose to happen when the labor market is what economists describe as “tight.”

The closely watched core PCE price index stood at 1.8% in December, a few ticks below the bank’s official 2% target for a the broader number that also includes food and energy.

The low rate of inflation is by no means an exception, however. It’s now the norm. The core PCE hasn’t topped 2.6% since 1993 — some 26 years ago.

“Core inflation has been pretty close to 2% for three decades,” said Sal Guatieri, senior economist at BMO Capital Markets.

Too much success?

The prolonged absence of ruinous price pressures largely reflects one of the Fed’s great achievements: Vanquishing the high double-digit rates of inflation in the late 1970s that threatened to topple the U.S. economy. Even as recently as the early 1990s inflation topped 4%.

The sustained success of the Fed has convinced Wall Street DJIA, -0.05% traders, Main Street business owners, corporate chieftains and American workers that inflation won’t get out of hand again. Employees no longer seek exorbitant pay increases to protect themselves against inflation as they did in the 1970s. Suppliers and producers have had less reason to jack up prices.

The Fed might have succeeded too much.

During and after the Great Recession, the central bank took unprecedented actions to stimulate the economy and lift inflation from potentially dangerously low levels. Only sporadically, however, has inflation risen above the Fed’s 2% target that it considers optimal for the economy.

Hence the Fed’s decision to adopt what Powell calls a “patient” approach.

“Powell has said that our models are not working now,” noted Luke Tilley, chief economist of Wilmington Trust and a former Fed advisor. “He’s essentially said if your models are not working, take a wait-and-see approach.”

The bank wants to see more evidence — clear and overwhelming evidence — that inflation is really heating up before it raises interest rates again.

The Fed’s current benchmark rate sits at a range of 2.25% to 2.5%, up from near zero as recently as 2015. That’s still quite low by historical standards.

“Until the data forces their hand, they have taken a ‘let’s-see-the-whites-of-their-eyes approach,” said Neil Dutta, head of macroeconomics at Renaissance Macro Research. “They could wait a considerable time. It’s hard to see inflation surging ahead.”

Read: The economy is off to another shaky start in 2019, but it’s not about to collapse

Deflated world

If inflation remains subdued, it won’t just reflect the Fed’s past handiwork. Vast changes in the global economy have worked to tamp inflation in the U.S. and around the world.

The era of low inflation began, not surprisingly, just as a technological revolution in the early 1990s gave birth to the modern Internet and sped up the pace of automation. The Internet virtually eliminated vast price disparities in local markets and allowed for instantaneous price shopping while automation slashed the cost of making things.

The entry of China into the global trading system in the late 1990s added more downward pressure on inflation as multinational companies were able to tap into a vast supply of cheap labor and low production costs in Asia.

The devastation wrought by the Great Recession a decade ago has also left its mark. The anxiety and psychological scars from mass layoffs and a wave of business failures keeps workers for seeking higher wages and made consumers reluctant to pay full price for anything.

Companies, for their part, have sought to maintain profits more by cutting costs than trying to raise prices aggressively, lest they lose business to rivals in a highly competitive global economy.

“These forces can last a lot longer,” said Guatieri, who calls the process a tug-of-war. “They continue to keep a lid on inflation.”

What to do in uncertain times

The big question for Fed officials is determining just how long these forces can last.

Based on their forecasts for the economy, they think inflation is likely to remain low for years to come. If that’s the case, Powell’s strategy of patience is likely to guide the Fed going foward. Tilley said Powell has shown a degree of flexibility about inflation that many of his predecessors did not.

“The Fed feels like it doesn’t have anything to fear.”

Stephen Stanley, an economist who’s often been critical of what he views as the Fed’s lax stance, agreed.

“You can certainly see why the Fed has taken that approach. It’s been a long time since inflation has been above target,” said Stanley, the chief economist at Amherst Pierpont Securities. “The Fed feels like it doesn’t have anything to fear.”

What still worries economists such as Stanley, though, is that complacency will set in and leave the Fed too slow to react if inflationary pressures finally began to build toward troublesome levels.

What would it take to get to that point?

The economy would have to run hot — grow much faster than it’s capable — for an extended period. Workers would have to be more aggressive in seeking higher wages and businesses in trying to pass on higher prices. And the global economy would have to be start growing strongly again, exerting upward pressure on the cost of critical commodities such as oil, steel and lumber.

Eventually that day will come, economists say.

“Just because inflation has remained so low for so long doesn’t mean it will always remain that way,” Guatieri said.