President Donald Trump is again calling for a weaker dollar.

And that preference might now be starting to line up with market fundamentals, which means his pronouncements on the value of the currency could pack a lot more punch in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, according to Alan Ruskin, chief international strategist at Deutsche Bank.

Trump took aim at the euro EURUSD, +0.0530% “and other currencies” that he described as “devalued against the dollar, putting the U.S. at a big disadvantage,” in a Tuesday tweet that also folded in another round of criticism of the Federal Reserve.

A growing chorus of analysts have started to pencil in expectations for a weaker dollar in 2019, particularly as expectations grow for Federal Reserve rate cuts. Fed-funds futures, which six months ago were forecasting official interest rates to continue rising this year, now reflect trader expectations for as many as three cuts before year-end amid fears rising trade tensions could amplify a global economic slowdown.

If fundamentals favor a weaker dollar, Trump’s efforts ito talk down the currency may prove more effective in the future, Ruskin said, in a blog post.

Ruskin said a turn lower by the U.S. dollar isn’t yet affirmed, particularly with market participants getting ahead of themselves when it comes to 2019 easing expectations. But efforts to talk down the currency in a dollar bear market are likely to be more effective than in a bull market.

“It is one thing talking down a USD (U.S. dollar) that has an upward bias, it is another pushing on a currency market where the door is slowing opening toward USD weakness,” Ruskin said.

“The president’s tweets on the USD have the potential to have much more lasting impact in the coming election year,” he wrote.

Indeed, the dollar might be more of a talking point on the campaign trail in 2020. Democratic contender Elizabeth Warren, a U.S. senator from Massachusetts, earlier this month called for “more actively managing our currency value to promote exports and domestic manufacturing.”

Read: Elizabeth Warren calls for ‘managing’ the dollar, and a new agency, to create jobs

Trump last August did brag — on Twitter — that a strong U.S. economy had money “pouring into our cherished DOLLAR.” But analysts weren’t convinced it marked a change in the president’s preference for a weak currency.

Indeed, Trump’s frequent dollar bashing long ago signaled a break with a “strong dollar policy” that was followed or at least paid lip service by Democratic and Republican administrations for more than two decades.

Archive: Trump is waving adios to the longstanding ‘strong dollar policy’

While the ICE U.S. Dollar Index DXY, +0.00% , a measure of the U.S. currency against a basket of six major rivals, lost ground in 2017, it bounced back strongly in 2018 to rise by 4.4%. The U.S. Federal Reserve, to Trump’s eventual ire, continued to tighten monetary policy through the end of last year, helping to support the U.S. currency.

The euro, which accounts for nearly 60% of the DXY, is down around 0.6% so far in 2019. The euro rose 0.1% on Tuesday to $1.132. The euro has rallied 1.3% so far in June, trimming its year-to-date loss versus the dollar to 1.3%. The dollar, meanwhile, is down around 1% versus the Japanese USDJPY, -0.04% its other major rival, this year.

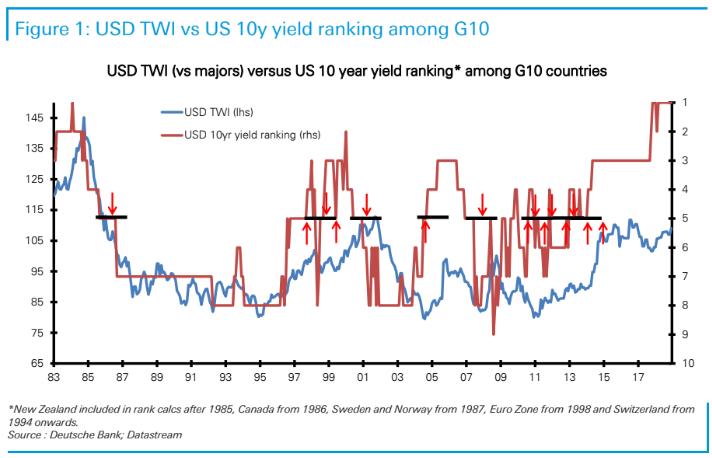

Ruskin said Deutsche Bank’s May calculations showed a euro that is cheap on a variety of trade-weighted measures. The dollar’s strength against an array of currency, meanwhile, makes euro/U.S. dollar misalignments more significant, he said. The dollar, on a trade-weighted basis, meanwhile, “can be fairly characterized as only moderately overvalued,” Ruskin said, attributing the dollar’s “solidity” largely to the U.S. having the highest ranking short- and long-term rates (see chart below) among the nations with the most heavily traded currencies and a steady current-account balance.

Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank

As for charges of currency manipulation, Ruskin said that while European Central Bank officials have begun to engage in “subtle jawboning” in recent years, particularly when the eurozone economy has appeared vulnerable, the institution has only intervened in markets when valuations were much more extreme.

Like others, Ruskin worried that a slowing global economy, subdued inflationary pressures and limited scope for central banks to ease will leave policy makers to view their exchange rates as a way to help ensure their monetary stimulus efforts remain effective.

That means macro conditions “are nicely set for what has colorfully been described as a ‘currency war,’ a currency race ‘to the bottom,’ or more specifically, weaker real [traded-weighted indexes],” he said.

That makes it important that the old Group of 20 rules against currency intervention, including jawboning, are affirmed when the G-20 leaders meet in Japan later this month. Such an affirmation would also be a rebuke of “currency-specific tweets,” Ruskin said. At least, as he noted parenthetically, “in theory.”