The proposed merger between blank-check company Churchill Capital IV and Lucid Motors is a pretty typical example of the pandemic SPACsplosion — it involves electric cars that have not yet been built, eye-popping forecasts and frothy trading.

And while this deal is not yet even completed, Wall Street has already gotten its share at a discount and retail investors have been hit with big losses.

Regulators and investors are finally figuring out the dangers of special-purpose acquisition companies, also known as SPACs, or blank-check companies. Lucid, a Tesla Inc. TSLA, +3.16% wannabe, and Churchill Capital IV CCIV, +4.00% have both been hit with several class-action lawsuits that allege Lucid Chief Executive Peter Rawlinson made false and misleading statements about vehicle production and revenue potential, an area the Securities and Exchange Commission is reportedly exploring as well.

Almost a month after news reports that Lucid was in talks to go public through a merger with a blank check company, Rawlinson told Forbes that he wanted to build 6,000 new Lucid Air vehicles in a factory in Arizona, potentially generating $900 million in revenue, and ramping up to 25,000 vehicles by 2022. Rawlinson touted similar projections in other interviews read by retail investors who jumped on the chance to get the next buzzy EV startup, and by Feb. 18, according to the lawsuit, shares of Churchill had climbed to an all-time high of $58.

When the merger was announced in February, investors learned in a presentation document that Lucid now plans on 577 vehicles in 2021 and 20,157 vehicles in 2022.

But the pros on Wall Street had already stepped in. The actual merger also included a private investment in a public equity, or PIPE, deal that gave institutional investors shares at a much lower valuation than they were going for in the public markets, where individual investors were bidding up the price after media reports of a merger. Between the new vehicle projections, and the details of the PIPE, the stock plunged, costing speculators, three of whom became the subjects of a Wall Street Journal feature on individual investors losing during the current stock-market mania.

With its allegations of false statements and poor disclosures, Churchill/Lucid is far from alone. Shortseller Hindenburg Research has detailed potential false claims from hydrogen-fueled trucking company Nikola Corp. NKLA, +2.02% and electronic truck company Lordstown Motors RIDE, +5.01%, leading to Securities and Exchange Commission investigations and class-action lawsuits involving both. Blank-check company Atlas Crest Investment Corp. ACIC — now in the process of buying flying-taxi company Archer Aviation — disclosed in an SEC filing that Archer is the target of a serious trade secret theft lawsuit filed by Wisk, a joint venture of Alphabet Inc. co-founder Larry Page’s Kitty Hawk flying taxi company and Boeing Co. BA.

Read more: The rise of EV SPACs as the next version of the dot-com bubble

Regulators and lawmakers are jumping in as well. Some of the biggest SPACs — including DraftKings Inc. DKNG, +9.51% and Virgin Galactic Holdings Inc. SPCE, +4.39% — have been forced to restate their previously filed financial information in response to new SEC guidance. The SEC spotlight, which also includes a focus on the accounting methods for the warrants issued to early investors, seems to have been the trigger that finally froze the SPAC boom. Insider deals as part of SPACs are now the focus of a new SPAC ACT, a bill introduced late last month by U.S. Sen. John Kennedy (R., La.) that seeks to get the SEC to require more disclosures to give investors more transparency.

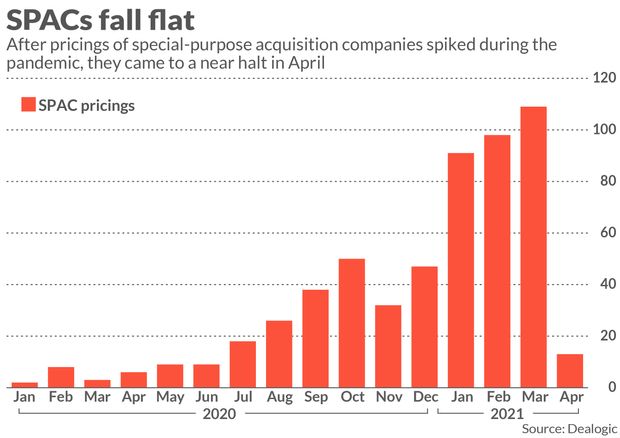

The result: A reckoning for the SPACsplosion. In April, the number of SPACs that filed to go public, or SPAC mergers that became public companies, skidded to a halt. Only 13 deals went public in April, raising $3.2 billion, according to data provider Dealogic, down from 108 SPACs in March, 97 in February, and 90 in January. In the first four months of 2021 combined, SPACs raised $323 billion in IPOs, nearly on par with full year 2020, when companies raised $336 billion, according to SPAC Research, but the flood has now slowed to a trickle.

“I think it slowed down to a degree because of the SEC statement on warrants,” said David Slovick, a partner at Barnes & Thornburg in New York, who represents companies involved in SEC and CFTC enforcement investigations and related regulatory counseling. “There is also a backlog at the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance, which is responsible for evaluating whether SPAC’s are accurately disclosing their financial information to prospective investors.”

The SEC’s recent reminders on its website have mostly focused on a few core issues with SPACs, with the underlying theme that some companies are playing fast and loose, apparently not seeing the de-SPAC process as a traditional IPO, especially when it comes to disclosures and forward-looking statements.

“Some — but far from all — practitioners and commentators have claimed that an advantage of SPACs over traditional IPOs is lesser securities law liability exposure for targets and the public company itself,” said John Coates, acting director, division of corporation finance, at the SEC, in an April public statement. He went on to say “Any simple claim about reduced liability exposure for SPAC participants is overstated at best, and potentially seriously misleading at worst.”

Read more: How the SEC is telling investors to ignore a billionaire’s legal advice

Besides SEC scrutiny, these companies now face that rush of class-action lawsuits. Currently, according to Stephen Blake, a litigation partner at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett in Palo Alto, over 40 lawsuits have been filed against SPACs in both federal and state courts of California, Delaware and New York.

“They are not frivolous cases, they are legitimate, substantive cases,” said Michael Klausner, a professor of law at Stanford Law School. “Will they have a general effect on the entire market? They could, but no time soon. It could be that a ruling in one of these cases, or more of these cases, could alter the way SPACs disclose, what they disclose and how they disclose it, but that will require a judicial opinion, which is months away.”

Klausner added that the SEC staff also could be looking much more closely at the projections SPACs or their acquisition targets are making, and say they have to justify the projections, which would constrain them one by one. “We will see whether they will do that or not,” he said.

The pattern of a recently created SPAC ETF SPAK, +3.85% shows how these stocks have lost their darling status on Wall Street. After peaking in February, the SPAC ETF, created last October and made up of 83 holdings — ranging from de-SPACed celebrities like Virgin Galatic Holdings SPCE, +4.39% and DraftKings DKNG, +9.51% to premerger status blank check companies like Churchill — has plunged 30% from its high. SPACs have also become a target of other shortsellers beyond Hindenburg Research.

When it comes to outlandish disclosures, with no fears of retribution, some SPACs may be taking a page from Chamath Palihapitiya, founder and CEO of Social Capital and recently called the “King of SPACs.”Palihapitiya said in a YouTube video that in a traditional IPO, you cannot give forecasts, but because a SPAC is a merger, “you’re all of a sudden allowed to talk about the future.”

One of Palihapitiya’s SPACs, Clover Health CLOV, +2.89%, was also the subject of a Hindenburg Research report, which concluded that the company’s “culture is rooted in deception and has taken every opportunity to push or break the rules to mislead its customers, investors, and Medicare.” The report also mentioned an undisclosed Justice Department inquiry, which Clover stated was not material and that as a healthcare company, it frequently receives requests from regulators.

Clover has disclosed an SEC investigation, which the company said is due to the Hindenburg report, and the stock is now trading around half of its December high of $16.77. A spokesperson for Clover Health declined to comment. Lucid Motors did not respond to requests for comment.

As hefty investor losses start to become a more familiar scenario in SPAC land, more lawsuits could follow. The recent focus by the SEC, combined with more litigation, will continue to hurt the prices of SPACs that completed their deals, often referred to as the de-SPAC. It could also have a chilling effect on the many SPACs that have not yet made an acquisition. SPACs have a two-year deadline to make an acquisition, or they have to refund the money they raised in their IPOs to investors.

SPACs are not going to suddenly go away. There is still too much money looking for a home, and SPACs remain an investment vehicle that is intriguing to many investors and startups — scooter-transit company Bird announced a SPAC merger this week, and there are literally hundreds of SPACs still out looking for candidates.

“There is no moratorium on people doing SPACs, or listing them,” said Slovick at Barnes & Thornburg. “Because there is so many of them they have exploded, and so much capital has gone into them. I do think the SEC is trying to slow things down, I think they are just being cautious.”

Hopefully, though, this slowdown and more scrutiny will help bring some common sense to this arena before too many more investors get hurt.