(Bloomberg) — Just months after Twitter Inc. and Facebook Inc. said they had removed hundreds of accounts used to undermine Hong Kong’s protest movement, the social media trolls are back.

Researchers at Astroscreen, a startup that monitors social media manipulation, have identified suspicious accounts that suggest take downs in August didn’t stop online activity targeting the protesters. Instead, some accounts with suspected links to the Chinese government that were removed have been replaced by different ones, engaging in similar types of tactics, the researchers said.

The findings highlight challenges Facebook, Twitter and Alphabet Inc.’s YouTube face in trying to dismantle disinformation campaigns that operate through their platforms. They also underscore growing concerns about governments and other political actors using social media platforms to sway popular opinion or silence their critics.

“This arms race between platforms and malign actors isn’t going away,” said Jacob Wallis, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s International Cyber Policy Centre, who authored a report on the matter in September. “Hyper-connectivity creates vulnerabilities that actors with various motivations will continue to exploit.”

Social media companies said they are working to curb campaigns to spread disinformation. Facebook is cooperating with other tech companies and security researchers to remove manipulation campaigns from its platforms, a spokeswoman said. A Twitter spokeswoman said platform manipulation has no place on its service, and the company will take enforcement action to stop it.

But keeping disinformation off platforms is proving no small task. Twitter said in August it had suspended 936 accounts linked to a China-backed operation, as well as a network of 200,000 other accounts. Facebook and YouTube announced similar moves the same month.

Still, researchers from Astroscreen, as well as Nisos Inc., FireEye Inc. and Graphika Inc., have found evidence suggesting that digital activity targeting the Hong Kong protests continued after the removals. They cautioned that gauging the scope of any kind of apparently coordinated, inauthentic activity — and tying it to China or any other entity — is difficult without additional data like IP addresses, which social media companies generally don’t disclose. While accounts may appear suspicious, it doesn’t mean they are controlled by any specific actor, such as a state.

In response to a request for comment, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs referred to an earlier statement by the Cyberspace Administration of China criticizing U.S. social media companies’ previous take downs as censorship.

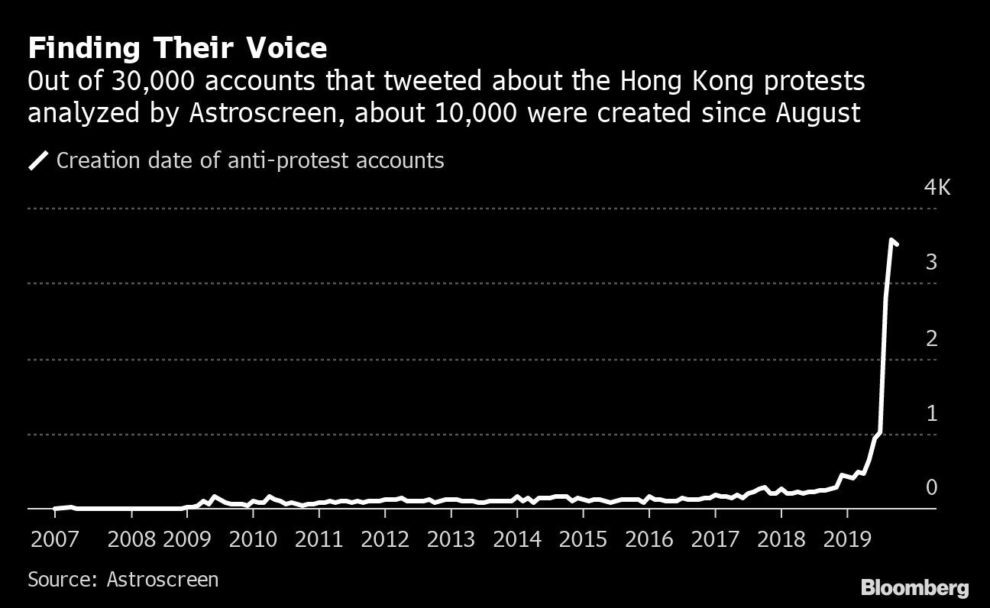

Astroscreen studied what it considered suspicious activity on Twitter. It analyzed 30,000 Twitter accounts that were against the protesters in Hong Kong and found that a third were created between August and October.

The recently-created accounts tend to follow a similar pattern, said Donara Barojan, who runs Astroscreen’s operations. Many have less than 10 followers, use a generic photo for a profile picture without providing an identity, and tweet primarily about the protests. Many post in English in an apparent bid to sway global opinion, she said. The accounts purged by Twitter were typically older, automated accounts that appeared to be bought on the open market and repurposed for targeting the protests.

Many of the Twitter accounts Astroscreen studied pushed Chinese state narratives, such as the idea that protesters are being paid by America or other foreign actors. The accounts use generic hashtags like #HongKongProtest or #HongKong to avoid detection by Twitter, and retweet official media videos or articles with added phrases that toe the Chinese state line, Barojan said.

This tactic is a “way to discredit the protest movement and provide popular messaging that people around the world who are against American intervention can identify with,” Barojan said. “It creates a false consensus, a key tactic of propaganda actors.”

None of the accounts highlighted in the embedded images responded to messages seeking comment. At least two have since been removed by Twitter.

Researchers at cybersecurity firms Nisos and FireEye said they too found evidence that new accounts resembling the disabled accounts became active in anti-Hong Kong protest content following the August take downs.

Creating new accounts is a “low cost, low risk,” move for trolls, according to Cindy Otis, a former Central Intelligence Agency officer who serves as the director of analysis at Nisos. “There is no incentive for them to stop trying.”

The accounts she found used tactics such as copying and pasting messages or retweeting them, and using memes and images to paint the protesters as violent, Otis said.

FireEye began tracking a disinformation campaign across multiple platforms in June, said Lee Foster, a senior director at the firm. Shortly after accounts were removed from social media companies in August, Foster said he saw accounts pop up that appeared to be related to campaigns that had been removed. They engaged in the same kind of activity and mimicked the tactics used by the removed accounts — suggesting that the people behind the information operation were not deterred, he said.

In a separate example following the social media take downs in August, Graphika, a company that uses artificial intelligence to map and analyze information on social media, found a spam network intermittently posting anti-Hong Kong protest material across YouTube, Twitter and Facebook, said Ben Nimmo, the company’s director of investigations.

Protesters aren’t the only target. Apple Inc. initially took heat from anti-protest accounts for allowing an app that tracked police whereabouts into its App Store. When the company changed course and removed it, Apple was targeted by protest supporters. A similar attack was waged against the NBA after Houston Rockets General Manager Daryl Morey posted a since deleted tweet in support of the protests, according to Astroscreen’s Twitter study. Over the course of 12 hours following his tweet, Morey was mentioned in more than 16,000 tweets, according to Graphika’s Nimmo.

Most were direct replies to Morey and many contained disparaging responses including the letters NMSL, Chinese internet slang for “your mother is dead.” Morey and the NBA didn’t respond to requests for comment. Morey has said he didn’t intend to cause any offense.

–With assistance from Qian Ye.

To contact the reporters on this story: Shelly Banjo in Hong Kong at [email protected];Alyza Sebenius in Washington at [email protected]

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Peter Elstrom at [email protected], Andrew Martin

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com” data-reactid=”71″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.