(Bloomberg) — The U.S. government’s antitrust case against Google follows a similar path to its attack on Microsoft Corp. more than 20 years ago — and that should make the internet giant nervous.

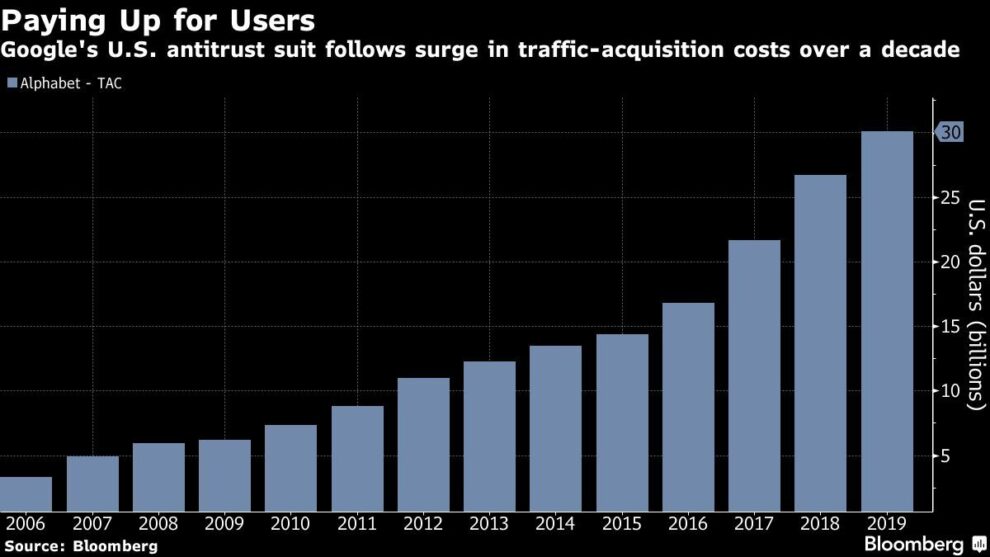

The suit focuses on payments Google makes to ensure its search engine is the default on mobile phones and web browsers. Google’s dominant market share and massive revenue allows it to spend billions of dollars a year on these deals, blocking out competitors from the valuable placements and limiting consumer choice, the Justice Department alleged.

It’s a similar argument the government made against Microsoft when it alleged in 1998 that the software company was requiring computer makers to set its web browser as the default on their machines. That lawsuit dragged on for years, distracted executives and helped Microsoft competitors — Google among them.

Shares of Google parent Alphabet Inc. rose after the complaint came out as analysts argued getting rid of the payments may save the company money. But antitrust experts said the government’s case lays out a straightforward path to beating the tech giant in court.

“The choice to mimic the successful strategy in Microsoft makes sense,” said Rebecca Allensworth, a law professor at Vanderbilt University. “The complaint focuses on a simple story that fits neatly into existing antitrust doctrine, does not require the adoption of novel theories of competition law, and avoids a ‘kitchen sink’ problem of listing all the potential ways in which Google acts in anticompetitive ways.”

Read the full complaint against Google here.

The Justice Department will try to paint a simple picture of Google using these default deals to block search rivals, while the company’s argument is more complex, according to Dan Wang, an associate professor at Columbia Business School.

“The burden in many ways is on Google to show how its complex technology is benefiting consumers,” he added. “They must explain how Google’s scale improves the search engine and why there should be one main provider. This will be hard in court.”

Google was quick to defend itself. The search distribution agreements it signs are similar to when a cereal brand pays a grocery store to appear on prominent end-cap displays at the end of aisles or an “eye level shelf,” Kent Walker, Google’s senior vice president of global affairs, argued in a blog post. Consumers have easy access to Google competitors, they just choose the search engine because it’s the best, he added.

That’s not quite right, said Gary Reback, an antitrust lawyer with Carr & Ferrell LLP who has argued against the power of Microsoft and Google for years. Google has 90% of the search engine market and is a household name, so it won’t be difficult to establish that the company has a monopoly, Reback said.

“It’s not just Google has a better shelf and its competitor is on the next shelf,” Reback said. “It’s that Google has all the shelves and its competitor is in a different store in a bad neighborhood 400 miles away.”

Google also stressed that its conduct doesn’t raise prices for consumers, and said changing the way it does business may actually increase prices. For example, it has given its Android operating system free to phone makers that agree to pre-install Google services including Search and Chrome. If it can’t make money that way, it would be forced to charge for Android. Indeed, when European regulators cracked down on these Android deals in 2018, the company started charging phone makers to license the Google suite of apps.

However, the U.S. government’s case, just like the Microsoft lawsuit before it, doesn’t have to specifically prove that Google’s behavior increases prices, said John Newman, who teaches antitrust law at University of Miami School of Law.

The harm to consumers isn’t higher prices but harm to innovation, which was the same allegation in the Microsoft case, he said. “There is harm to the competitive process,” he said. “That’s running throughout this complaint. To me it’s pretty compelling.”

And just because the government’s case is narrowly focused on search distribution agreements, it doesn’t mean that the end result of the lawsuit would be confined to banning those deals, Reback said.

The government left itself lots of leeway to propose remedies. It asked the court to consider major changes to fix the competitive landscape such as “structural relief” — a legal term that includes forced spinoffs or breakups.

Ryan Shores, a DOJ antitrust litigator and senior advisor for technology industries, echoed that warning during a call with reporters Tuesday. “Nothing’s off the table,” he said.

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.