As Uber prepares to report its quarterly earnings for the first time as a public company, investors and analysts will be looking for signals to answer one question: Will Uber ever become profitable?

The ride-hailing company reports earnings after Thursday’s closing bell. It has already projected a net loss of at least $1 billion for the first quarter of 2019 in an unaudited report released in a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission ahead of its IPO. That compares with the net income of $3.75 billion it reported for the same period last year. Uber estimated revenue for the quarter would range from $3.04 billion to $3.10 billion, compared with the $2.58 billion in revenue the company reported in the same quarter of last year.

Uber’s large losses had many analysts questioning its sky-high early valuation ahead of its IPO. The company had been seeking a valuation as high as $120 billion, according to early reports, as it recorded an adjusted EBITDA loss of $1.85 billion in 2018. Uber tempered expectations by pricing its IPO at $45 per share, giving it a market value of $75.46 billion at its IPO on a nondiluted basis. The stock still sank 7.6% on its first day of trading to a market cap of $69.7 billion.

Uber would argue its losses are the result of heavy investment in its core ride-sharing market and newer initiatives including meal delivery and freight. CEO Dara Khosrowshahi is fond of likening Uber’s trajectory to Amazon’s early days on the public market. Like Uber, Amazon debuted with losses in 1997, but its stock price has since ballooned and its net income grew to $3.6 billion in the last quarter. Unlike Amazon, Uber’s revenue growth has already begun to slow.

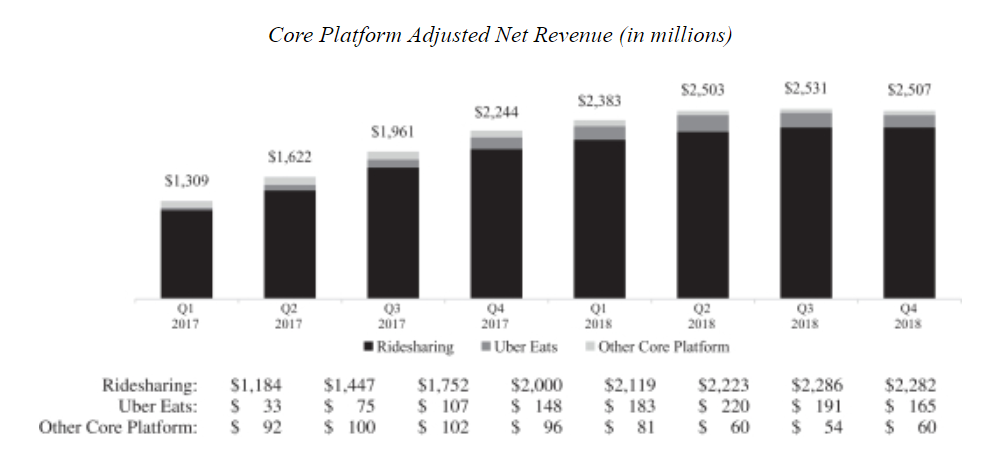

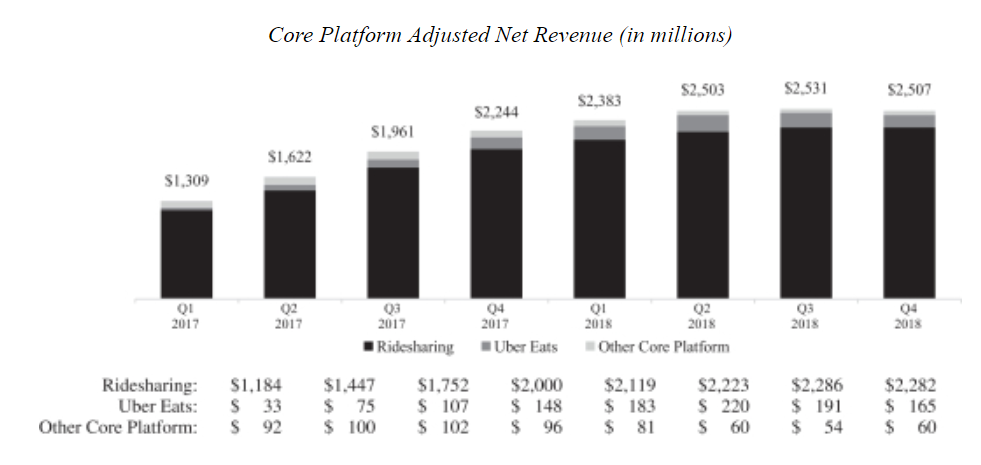

The company blames competitive pressure in ride sharing and the rise of its costly delivery business, Uber Eats, for the deceleration. Competition from services like Lyft has lowered Uber’s take rate, which it defines as gross bookings divided by adjusted net revenue.

Meanwhile, its delivery service Uber Eats is growing, but it requires the company to pay not only the drivers, like in its ride-hailing business, but also its restaurant partners. Uber said in its IPO filing it has “onboarded large-volume restaurants at a lower service fee and in geographies with greater competition, such as the United States and India.” As a result, it expects the take rate to continue to decline in the near term.

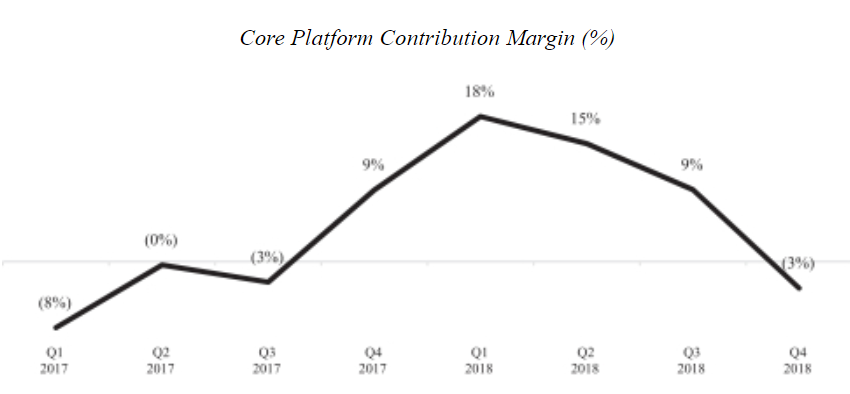

Uber’s core platform contribution margin, the amount of profit it makes from its core platform business divided by revenue, turned negative in the fourth quarter of 2018. The decline indicates Uber is actually on a path to become less profitable as it gains more customers and brings in more total revenue.

In an interview with CNBC’s Andrew Ross Sorkin that aired on Uber’s IPO day, Khosrowshahi defended the comparison to Amazon.

“It’s a fair comparison at the wrong time,” he said. “So a lot of private companies now are holding off much longer before they go public. We are much bigger, much more mature as a company as we go public, and if you do look at the growth rates, our audience is growing 33% on a year on year basis, transactions are growing 36%. To be able to grow transactions 36% on a $50 billion base is pretty incredible, and we hope to keep it going.”

Still, Khosrowshahi would not commit to 2019 being the company’s peak year for losses, as Lyft’s executives had days earlier on their earnings call.

“That would be our intention, although there can’t be any guarantee,” Khosrowshahi said.

While profitability may still be a ways away for Uber, analysts are looking for signs of growth in Uber’s gross bookings and take rate. Uber has substantially grown its gross bookings, defined as the full dollar value of an Uber service, for both ride sharing and Eats. Gross bookings for Uber Eats more than doubled from $3 billion in 2017 to $7.9 billion in 2018, according to the company.

But while its ride-sharing take rate saw a small uptick from 21% in 2017 to 22% in 2018, Uber Eats’ take rate has been driven down due to greater driver incentives and expansions to new areas, according to the company. The take rate for Uber Eats declined from 12% in 2017 to 10% in 2018.

Lyft executives offered a glimmer of hope for the overall ride-hailing industry on their first earnings call. President John Zimmer told analysts “this is the most rational the market has been,” meaning ride hailing companies may be able to keep drivers on their platforms with lower incentives — a key cost driver for both Lyft and Uber.

In a note Tuesday, Wedbush Securities analysts outlined some of the positive signs they are looking for in the report.

“While investors have been expecting take rate compression as competition pushes irrationality and rider incentives in the near-term, we expect a focus on a path to improvement and accelerating revenue growth over the remainder of 2019 and into 2020,” they wrote.

Watch: CNBC’s full interview with Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi ahead of its IPO