When you go to the supermarket, you may have some inkling about how Alice in Wonderland felt. Your favorite products on the shelves appear smaller than you recalled.

OK, that might be a bit of a stretch, but you’re certainly not going crazy if you’re noticing that a box of cereal doesn’t last as many breakfasts as it once did or if your dishwasher pods are smaller.

It’s a sign of the times as inflation is at a 40-year record high, and companies that make some of your favorite foods, cleaning products and household goods are seeing their production costs rise as a result.

These companies can pass the costs on to consumers by raising prices. Or they can do something a bit more sneaky: shrink the contents of a product to maintain the same price — a phenomenon known as “shrinkflation.”

Noah Davis, pictured, began noticing shrinkflation around five months ago when an Amy’s pizza that usually fed three of his children was only enough for one, he said.

Photo courtesy of Noah Davis

Noah Davis, a Seattle-based attorney, said he started noticing shrinkflation about five months ago. It began with an Amy’s Margherita frozen pizza, which sell for about $8, depending on the retailer. One pie, which used to feed three of his children in the past was only enough for one child, he said.

“You open the box and there is this tiny shrunken pizza inside,” Davis, 50, said. Amy’s didn’t respond to MarketWatch’s request for a comment.

Then he noticed the same was happening with orange juice, protein bars, cereal, and Tillamook ice cream sandwiches, which currently sell for $3.99 for a pack of four 3-ounce bars at Albertsons ACI, +0.34%.

Tillamook didn’t respond to MarketWatch’s request for comment, but the company said on Twitter TWTR last year that rising costs had forced it to shrink its ice cream sandwiches to 3 ounce from 3.5 ounces, and it published a blog post explaining its decision to make its ice-cream products smaller.

“‘You open the box and there is this tiny shrunken pizza inside’”

“We’ve recently changed the size of our ice-cream container, so that we can keep delivering our beloved extra creamy ice cream to our fans without sacrificing any of the quality components that got us here,” the company website says.

“Smoke and mirrors,” Davis said.

His experience with ever-smaller products lately is hardly unique. In fact, there is an entire Reddit thread where users document products they believe have shrunk.

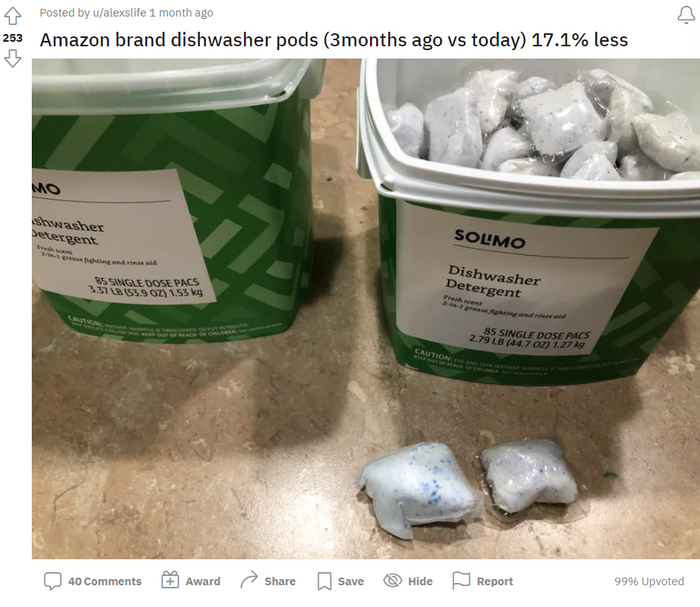

That includes Amazon’s AMZN, +0.02% house brand dishwasher pods, Truth protein bars, General Mills’ GIS, +0.44% Golden Grahams cereal and more.

A photo posted on Reddit’s forum about shrinkflation, appearing to show Amazon’s Solimo detergent pods getting smaller.

Uncredited

General Mills didn’t say whether the portion changes were a result of inflation. The company said it is part of an ongoing effort “to create consistency and standardization across our cereal products, making it easier for shoppers to distinguish between sizes on shelf,” said Kelsey Roemhildt, a General Mills spokesperson.

“The majority of the portfolio has been through the changes,” she added.

Truth Bar creator Diana Stobo, who became the owner of the brand in June, said she had to reduce the size of the bars from 50 grams to 45 grams in order to stay profitable “due to the increasing costs of quality ingredients.”

But the smaller bars still have the same amount of Omega 3s and probiotics as the 50-gram bars, she told MarketWatch.

Amazon did not respond to MarketWatch’s request for comment.

Shrinkflation was a thing in the 1970s

There are instances of shrinkflation dating back to the 1970s.

A 99-cent pack of Woolworth 30 pencils in 1973 became a 99-cent pack of 24 pencils in 1974, and gumball makers reduced the size of their candy when the price of sugar increased in the 1970s, according to historian Stephen Mihm.

The down-sizing was especially necessary since it would’ve been more costly to construct new gumball machines to accommodate different coins if gumball makers raised prices.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics takes these size changes into account in its monthly Consumer Price Index report on inflation, said Steve Reed, a BLS economist who oversees the report.

“If the price of a product the BLS is tracking doesn’t change but the size or quantity does ‘we will convert the price change to a per-unit amount’”

To gauge the level of inflation Americans are experiencing, the BLS tracks price changes for a fixed basket of roughly 80,000 goods and services ranging across 200 different categories.

Items or brands that consumers are more likely to buy than others are given more weight when it comes to calculating the overall price level change each month. The same applies to expenses that represent a bigger chunk of the typical U.S. household’s budget, such as housing.

In doing so, the BLS also keeps track of the size and quantity included for a given product.

So if the price of a product being tracked doesn’t change, but the size or quantity decreases, “typically if it’s a small change we will convert the price change to a per-unit amount,” Reed told MarketWatch.

For instance, if a 64-ounce container of orange juice is included in the sample yet BLS economists are only able to find information about a 59-ounce container for the same price, “it would be computed as an 8% price increase,” said Reed.

Despite these efforts, it’s impossible to differentiate the extent to which shrinkflation is driving inflation versus traditional price increases when combing through the CPI report, Reed added.

Some of your go-to products may be shrinking in size, although it’s happening in a more subtle way than illustrated here.

MarketWatch photo illustration/iStockphoto

Raising prices vs. shrinkflation

If it were up to most companies, they wouldn’t reduce the size or quantity of their products, said Scott Rick, a marketing professor at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business.

In other words, they’d ideally like to stay profitable at a constant price or size of a given product. But realistically, that is impossible.

Even though shrinkflation “can feel sneaky,” Rick said, “it’s not unethical.”

“‘Just because a box of Cheerios is $4 today, it’s not an eternal commitment to always sell that amount of cereal for that price forever’”

“It’s not like you’re breaking the terms of some contract.” The same goes for price increases, he said. “Just because a box of Cheerios is $4 today, it’s not an eternal commitment to always sell that amount of cereal for that price forever.”

But when it comes to iconic products like a six-pack of beer or a 12-pack of Coca-Cola KO, +0.07%, you can be certain that you won’t be seeing a five-pack of beer or an 11-pack of Coke, and instead, a price increase.

Toblerone maker Mondelez MDLZ, +0.17% made this mistake in 2016 when it increased the gap between the chocolate triangles on its candy bar to avoid raising prices as a result of rising ingredient costs, Rick told MarketWatch.

The decision angered consumers who compared the new version to a bike rack, leading the company to revert back to the original Toblerone version two years later.

(Mondelez did not respond to a request for comment.)

How to shop smart with shrinkflation

Chances are when you go to a grocery store, you don’t have enough time to carefully research every item you’re buying to see if a manufacturer shrunk the size of a product and if so, by how much.

At the same time, having that information could lead you to make better decisions. That’s why Phil Lempert, a food-industry expert who founded SupermarketGuru.com, recommends saving your grocery store receipts.

Most supermarket receipts actually give the product name, the weight and/or the size of the package. And, of course, many packages will give you the price per item or price per unit of weight to allow you to compare.

When you make your food shopping list, highlight the items on your old receipts that you plan to buy again. Lempert said he uses that “as my benchmark to look what I paid last time and also the size of the package.”

That’s about the only way to avoid surprise shrinkflation “unless we have extraordinary memories of the size of the package the last time around,” he said.