When Greenville, N.C.’s North State Little League team made a 2017 World Series run, nothing was going to stop approximately 2,000 friends, family and supporters from traveling almost 500 miles north for the televised tournament — certainly not money.

Businesses in the city — where the median household income is $36,500, compared to the national median of $57,652 — chipped in so all the families could afford the roughly 20 nights of hotel stays for various tournaments, said Brian Weingartz, the city’s Little League commissioner. “People rallied around them and helped to do what needed to be done,” he said.

‘People rallied around them and helped to do what needed to be done.’

Greenville is a small city with two baseball leagues, both started in the early 1950s and still going strong. The 2017 team finished second among the American teams. Greenville also sent a team to the World Series in 1998.

It costs $95 for children to participate in the city’s Little Leagues. Greenville’s fee is below the average of $150 for Little League registration costs nationwide — though registration can cost $30 in some cities and up to $250 in some suburbs, according to WinterGreen Research, a firm monitoring the youth sports industry.

Fees typically cover hat, team shirt and operating costs, which include money to maintain fields and staff games with umpires.

But teams from relatively less-wealthy towns like Greenville making it to the Little League World Series are becoming a rarity, a MarketWatch analysis suggests.

The Little League World Series, which starts Thursday, celebrates Americana and youthful athletic glory. The South Williamsport, Pa.-based tournament is also a glimpse into a different American story right now: income inequality.

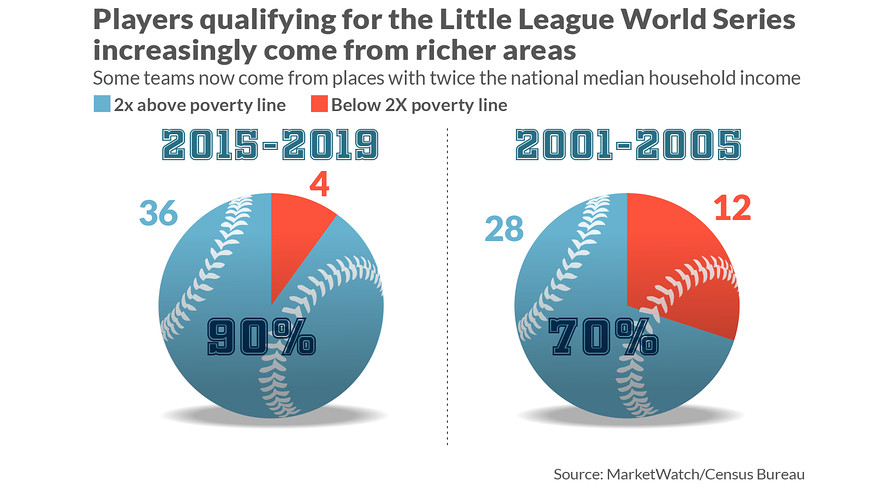

Between 2015 and 2019, approximately 90% of the American teams playing in the series came from places or had leagues based in zip codes with median household incomes roughly twice the poverty-line threshold, up from 70% between 2001 and 2005, also roughly twice the poverty-line threshold during that period.

Between 2015 and 2019, approximately 90% of the American teams playing in the series came from places or had leagues based in zip codes with median household incomes roughly twice the poverty-line threshold, up from 70% between 2001 and 2005, also roughly twice the poverty-line threshold during that period.

What’s more, 10 of the 40 teams originated from locations with median household incomes nearing $100,000 a year or above between 2015 and 2019. From 2001 to 2005, five of the 40 teams had median household incomes nearing or above approximately $70,000 a year, comparable to today’s $100,000 mark at the time.

Tom Farrey, the executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Sports & Society Program, said he wasn’t surprised by MarketWatch’s findings. An increasing number of baseball fields in lower-income areas are in disrepair because many local officials have been slashing their parks and recreation budgets since the Great Recession, he said. If fields are dilapidated, families have to pay for their children to play elsewhere, he said — or they don’t play at all.

The rise of travel leagues could also help explain why fewer low-income towns are making it to the Little League World Series, he said.

These economic barriers worry some observers. Youth sports can play a role in helping children way beyond trophies. For one thing, they help teenagers get past traumatic childhoods, according to a recent study released by the University of California, Los Angeles. Researchers said men and women who played team sports — from soccer to cheerleading — had lower diagnosis rates for anxiety and depression, and better mental health.

A RAND Corporation study in July study pinpointed a $50,000 annual household income as the dividing line between families whose kids participated in school and club sports leagues and those whose kids didn’t.

Just 52% of children from lower-income families participated in organized sports, compared to two-thirds of children from middle- and higher-income families.

The RAND study said prohibitively high costs were the top reason (42%) why families making less than $50,000 didn’t enroll their kids in sports, while the time commitment was the top reason (45%) families earning over $50,000 a year opted against sports for their kids.

Just 52% of children from lower-income families participated in organized sports, compared to two-thirds of children from middle- and higher-income families, RAND said. (The think tank defined lower income as below $50,000, and counted middle and higher income as anything above that point.)

Little League still starts with games within one community, and the very best can make it to the World Series. But there are other forms of youth baseball, including more expensive travel teams that bring together players from a wider area. Many Little League players also likely played on travel teams, Farrey said.

Travel is now the largest single annual expense families make on youth sports, according to the Sports & Society Program’s Project Play. Families spend an average of $196 per sport, per child on travel, said its research. Average equipment costs are second, at $144.

Project Play earlier this month launched an initiative called Don’t Retire, Kid, a six-figure public awareness campaign aiming to increase youth sports participation rates and bring attention to issues like climbing costs.

Organized sports don’t come cheap

A family typically spends $693 annually on sports equipment, travel and costs, according to Project Play. Some sports cost much more. Typical ice-hockey costs are almost $2,600. Average baseball costs are $660, although some wealthier parents spent at least $12,000 so their children could play baseball.

Little League International, the umbrella group overseeing the tournament and other softball and baseball competitions, said it has programs addressing cost barriers. Its Little League Urban Initiative operates approximately 200 leagues. The organization’s Grow the Game Grant Program has paid more than $3.5 million to 200 leagues worldwide since 2015, spokesman Kevin Fountain said.

See also: Parents are going into debt over their kids’ extracurricular activities

The organization has also cut fees over the years to keep costs down. For example, local leagues have to pay Little League annual charter fees for every team it brings together. In 2015, Little League cut charter fees to $10 from $16, Fountain said.

The American youth-sports industry has grown 13%, from $15 billion to $17 billion between 2017 and 2018, according to Susan Eustis, president of WinterGreen Research. The industry could reach $29 billion by 2025, she said.

Farrey hopes that more is done to ensure that Little League and all organized sports are as inclusive as possible for low-income families. “Sports tourism has become big business,” he said.

Add Comment