Unlike other major purchases in life, families know little about what they will actually pay for a college education when they begin the search.

Without clarity on the eventual price, families think more about the academic and social fit of campuses rather than the financial fit. They believe, often incorrectly, that they can figure out a way to pay the cost through a combination of scholarships, loans, and savings. After all, they’ve heard that every school offers a discount to entice you to enroll (hint: they don’t).

As a result, emotions steer choices, and many wind up disappointed when the hoped-for financial aid doesn’t materialize.

During the year I spent inside the admissions process, what I came to see, and prospective students and their families should too, is that colleges are either “buyers” or “sellers” of spots in the freshman class.

Sellers are the “haves” of admissions. They have something to sell that consumers want, typically a brand name that signals prestige in the job market and social circles. They are overwhelmed with applications, many from top students. Their admissions officers see their role as gatekeepers. You’ve heard of these places: Stanford University, Amherst College, Yale University, among others.

The buyers are the “have-nots” in terms of admissions—although they might provide an excellent undergraduate education. They may lack national reputations or have much smaller endowments. Rather than select a class, their admissions officers must work hard to recruit students to fill classroom seats and beds in dorm rooms, so they offer coupons on tuition called “merit scholarships” no matter your family’s income.

You’ve heard of some quality schools—Clemson and Syracuse universities, for instance— but perhaps not others, such as Elon University in North Carolina and Rollins College in Florida.

Whether a college is a buyer or seller matters to applicants for two reasons. First, getting past the gatekeepers at the sellers is becoming increasingly difficult. Many applicants to top-ranked schools all have a 1400 or 1500 on the SAT, a 4.0-plus grade-point average, and a dozen AP classes and extracurricular activities. If students have only sellers on their list, they risk getting rejected from every school they apply to. Then what?

Second, sellers don’t need to buy students with tuition discounts to fill their classrooms. They are prestigious enough that a large percentage of families are willing to pay full price. At Yale, for example, 48% of undergraduates pay the full $74,000 sticker price for tuition, room and board. Most sellers offer financial assistance only to students who really need it or are truly exceptional.

Yet many families find themselves making too much to qualify for significant need-based aid but not enough to write a check for tuition—and for four years of it. The federal government formula, for instance, suggests a family earning $200,000 a year will contribute roughly $50,000 a year for college. Students and their families only find out in April – after acceptances roll in – what they’ll actually have to pay. All too often, this financial reality puts a prestigious acceptance out of reach for students and their families. That can be an even bigger blow than a rejection.

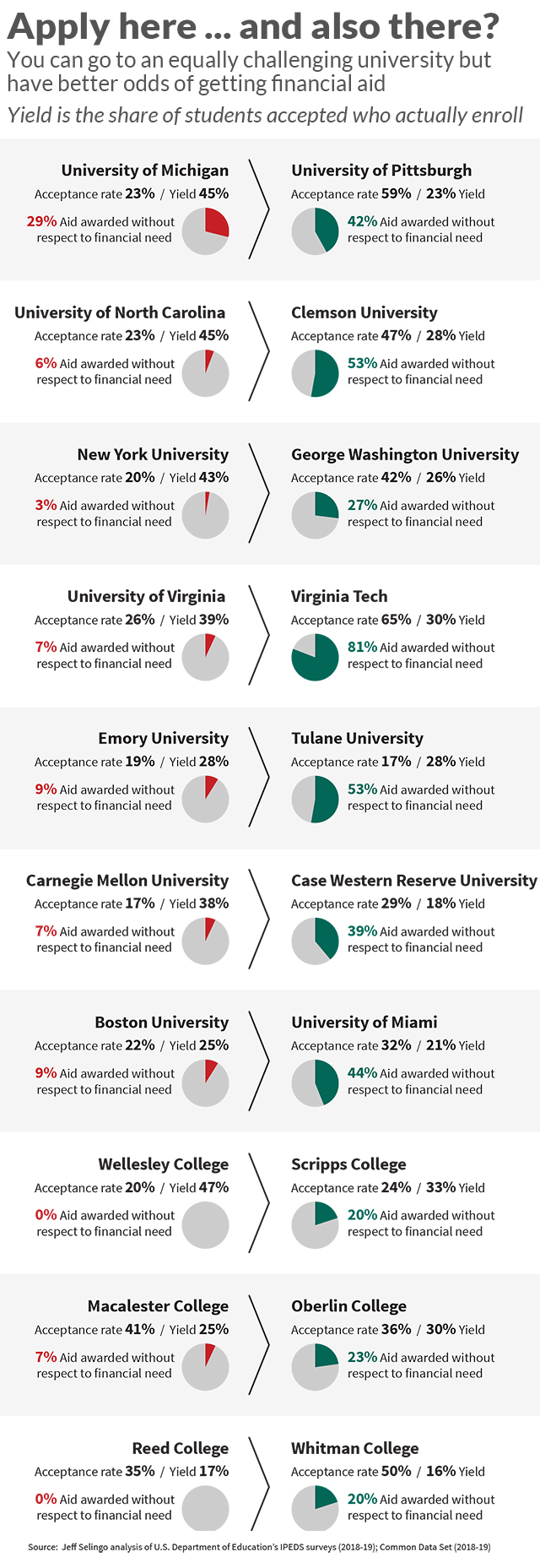

To discover whether a college is a buyer or seller, look at the percentage of applicants it admits, the percentage of those who choose to enroll (the yield rate), and the percentage of institutional aid that is given out without respect to an applicant’s financial need. The lower the admit rate, the higher the yield, and the larger the percentage of aid based on need, the more likely the school is a seller. You can find this information on a school’s Common Data Set questionnaire (found via an internet search) or simply ask them.

Savvy students willing to look beyond the brand-name sellers can find great schools that are buyers. Compare, for example, two private, urban universities in the south. Emory University in Atlanta, with a sticker price around $70,000 a year, accepts less than one-fifth of applicants and spends less than 10% of its financial aid on merit-based discounts. Emory is a seller. New Orleans-based Tulane University, with a nearly identical sticker price, spends more than half of its institutional aid budget on merit-based aid. Yet both schools attract top-tier students with average SAT scores near 1500.

One senior I know had her heart set on Wellesley College outside Boston and got accepted, but couldn’t go because she didn’t get any aid. In my terms, Wellesley is a seller. If she had Scripps College (in California) or Oberlin College (in Ohio) on her list, her chances for a discount would have been better.

Sellers make up less than 10% of four-year colleges and universities. To ensure students end up with the right financial fit, they should have a mix of buyers and sellers on their list.

Some high-school seniors overload their list with sellers because they think the name will look good on the sticker affixed to the rear window of the family car. My advice: add a wider range of places to your list—including some buyers—and next spring you’ll be a lot happier with whatever college logo you put on the car.

Jeffrey Selingo is the author of “Who Gets In and Why: A Year Inside College Admissions,” from which this essay is adapted. He is the former editor of the Chronicle of Higher Education and a special adviser and professor of practice at Arizona State University. Follow him on Twitter @jselingo.

Add Comment