This week’s main event takes place on Friday, when Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell kicks off the Kansas City Fed’s annual economic symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyo. Financial markets will be listening closely for hints about the near-term direction of monetary policy.

How will Powell finesse the bond market’s expectations for significantly lower interest rates with policy makers’ more modest intentions? Is the Fed supposed to appease the markets, fearful of another major stock market selloff, like the one that followed the Dec. 19 rate hike, or another plunge in long-term yields?

Or is the Fed supposed to say, and do, what it thinks is appropriate, and the fallout be damned?

The question as it relates to the current situation is easier to answer than the generic one, so let’s start with the here-and-now. The Fed needs to cut rates without further delay because policy is too tight as signaled by the bond market.

Decidedly unnatural

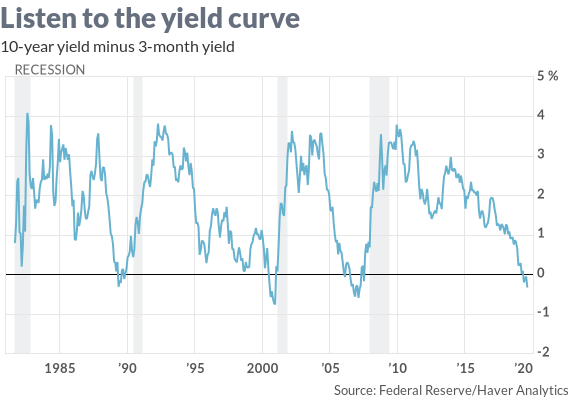

The spread between the pegged policy rate, or a proxy, and the 10-year Treasury TMUBMUSD10Y, -0.53% yield turned negative three months ago. Inversion is a decidedly unnatural state and precursor, albeit with a long lag, of recession.

Why unnatural? Because investors normally demand greater compensation to lend money for 10 years than overnight or for a few months. It’s only when investors think that short-term rates will be markedly lower for the foreseeable future that they will accept a lower rate on a 10-year security than on a short-term Treasury bill that would have to be rolled over at the prevailing rate every few months.

Inversion violates the natural order of things and needs to be rectified by the central bank. After all, it’s not nice to fool, or in this case defy, Mother Nature.

Now, we have all heard the adage that monetary policy works with long and variable lags. Which is why the Fed relies, or should rely, on forward-looking indicators when deciding on the appropriate policy course.

It just so happens that financial markets convey just that kind of information. The term spread is one of 10 designated leading economic indicators. In fact, it boasts the longest lead time, inverting 13.5-14 months, on average, before the peak of the business cycle.

Fed policy makers seem to tout the yield curve when it is positively sloped as something to keep an eye on should it turn negative — and then ignore it, or find excuses as to why this time is different, once it inverts.

Screaming for lower rates

The bond market is screaming for lower rates — and has been since the Fed’s Dec. 19 rate hike and its projections for two more this year, and Powell’s disastrous press conference, where he affirmed that “the balance sheet runoff (is) on automatic pilot.”

The response? “The S&P 500 had its worst reaction to a Fed announcement of some (policy) action since Volcker’s 1979 Saturday night massacre,” said Jim Bianco, president of Bianco Research. “The second worst was on July 31. So Powell has two on his watch.”

It was during a rare-at-the-time press conference on Oct. 6, 1979, that newly appointed Fed chief Paul Volcker announced that the central bank would shift its focus from managing the overnight interbank rate to managing the supply of bank reserves to rein in inflation.

At Powell’s July 31 press conference, what seemed to irk the bond and stock markets was his reference to the 25-basis-point reduction in the federal funds rate to 2%-2.25% as a “mid-cycle adjustment to policy,” not part of an open-ended easing campaign.

So yes, the Fed needs to heed the message emanating from the bond market right now and act pre-emptively to avert a further slowdown in economic activity.

Prisoner of the markets

The generic question of whether the Fed should be a prisoner to the markets is a bit more difficult to answer, especially when phrased that way.

“If you believe the market is, to some degree, a reflection of economic reality, then the answer is yes,” Bianco said. “Yes, markets overshoot, but if you have the right policy, you don’t have to fight the market.”

“Most of the time, the market is in broad agreement with the consensus of economists and the Fed,” he said. “In those rare times like the present, when the market becomes the outlier, pay attention. The message should not be ignored.”

Fed funds futures contracts are telegraphing four more rate cuts in the next year. Both the Fed’s projections and economists’ forecasts are more conservative.

The stock market, which is near all-time highs, certainly isn’t sending out any recession warnings. And the stock market — specifically the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index SPX, +0.82% — is one of the 10 components of the index of leading economic Indicators.

Historically, the bond market has been a better predictor of turns in the economy. As Nobel-prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson famously quipped, the stock market has predicted nine of the past five recessions.

“Economists wish they were that good,” Bianco said, referring to the chronic failure on the part of dismal scientists, including those at the Fed, to forecast recession.

Not on board

It’s doesn’t sound as if members of the Federal Open Market Committee are on board with another rate cut right now.

Presidents Eric Rosengren of the Boston Fed and Kansas City’s Esther George dissented from the July decision to lower the benchmark rate. St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, who had dissented in June because he favored a rate cut at that time, indicated he might prefer to wait to see the effects of the July rate cut before taking additional action.

And, according to the minutes from the July 31 meeting, released on Wednesday, “a couple of participants” (two?) would have preferred a 50 basis point cut” in the funds rate while “several participants” (three?) favored no change in policy.

“Most participants” viewed a quarter-point cut as a form of insurance against a further decline in inflation from the Fed’s 2% target and, echoing Powell’s description, as a “mid-cycle adjustment” in response to downside risks from weaker global growth and uncertainty surrounding trade policy.

It’s not as if the financial markets are always pushing for a fix.

“From 2009 to 2015, the fed funds futures market was pricing in rate hikes, and the stock market was fine with it,” Bianco said. “The idea that the stock market is a junkie, that it will want more, more, more until it kills itself from an overdose is wrong.”

It is only when the Fed became the outlier, raising rates late last year, that the bond market started clamoring for rate cuts, he said. “This is the first time in the last 50 years that both the fed funds rate and three-month T-bill rate TMUBMUSD03M, -0.39% are the highest of any developed country.”

So don’t think of it as the Fed taking an oath of fealty to financial markets. Think of it as the markets conveying vital information that will guide the Fed in the conduct of policy.

Add Comment