Rudy Gutierrez

Rudy Gutierrez

This is the third in a six-part series of stories about programs that offer high-school students the opportunity to take college classes.

The series was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program. (Read parts one and two here).

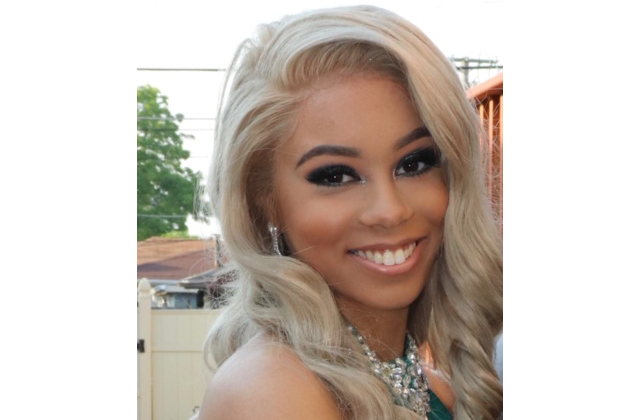

By any measure, Summer Baptiste is impressive.

The 18-year-old graduated from Chicago’s Kenwood Academy High School last year not only as her class valedictorian, but with an associate’s degree from City Colleges of Chicago.

Despite those accomplishments, Baptiste isn’t enrolled at her top choice college — and it’s not because she didn’t get in. When Baptiste began her college search, she was committed to attending a school where she’d get credit for the bulk of — if not all — the college courses she took in high school.

Baptiste had participated in what’s called a dual-credit or dual-enrollment program — where students take college courses during high school. She hoped to transfer as many of the credits she earned as possible to whatever college she attended.

“I knew from the jump that Ivy Leagues weren’t going to acknowledge any of the credits,” Baptiste said, so she didn’t even bother applying. Instead, Baptiste focused her college search on the tier of elite, selective schools just below the Ivy League.

‘I told my mom, ‘I didn’t work this hard two years in a row just for them to not acknowledge any of that.’

For a while, her strategy appeared to work. Baptiste was accepted to Emory University in Atlanta and she says she was assured by the school that about one year’s worth of the credit she earned in high school would transfer.

At the beginning of August, shortly before Baptiste was scheduled to start school, she called Emory to confirm that was still the case. She said she was told the school had a strict policy that would make it difficult for them to accept the bulk of the courses.

Courtesy of Summer Baptiste

Courtesy of Summer Baptiste

Emory considers college courses students take in high school for credit in certain circumstances, including when they’re taught at a college or university, though not at a student’s high school (Baptiste took college courses both within her high school and at a local community college), Laura Diamond, a spokeswoman for the school, wrote in an email. The school communicates this information to students through its admissions website, Diamond wrote. (She said it was the school’s policy not to comment on a specific student’s case.)

Baptiste was “highly upset” when Emory informed her the credits wouldn’t transfer. But she wasn’t willing to give up the college credit she earned in high school. “I told my mom, ‘I didn’t work this hard two years in a row just for them to not acknowledge any of that,’” she said.

She decided not to attend Emory.

Instead, she and her family “pulled as many strings as we could,” and she enrolled at the University of Illinois-Chicago — the day before classes started.

The school took 100% of Baptiste’s credits.

Transferring college credits earned in high school isn’t always seamless

With college costs and student debt rising, policy makers and education leaders have touted the potential of giving high-school students the opportunity to take college courses to curb the amount of time and money they spend on their journey to a degree.

But even as the programs have exploded — in some cases explicitly advertised as an antidote to our nation’s college-affordability problem — there’s limited evidence on how the college credits students earn in high school are applied toward their college degrees and whether they wind up saving the students money.

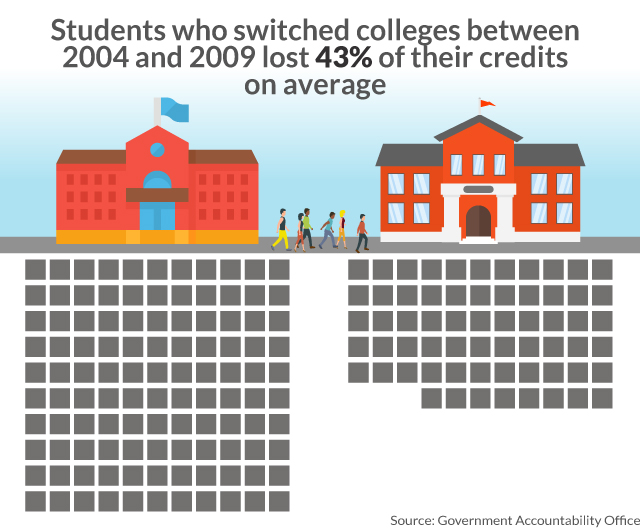

Students who switched colleges between 2004 and 2009 lost 43% of their credits on average, a 2017 report from the Government Accountability Office found.

Researchers are beginning to look more closely at how these courses affect the amount of time and money students spend on a degree. In some cases, the findings have been promising, but rarely definitive.

Students who graduated from a four-year college in Texas who took college courses while in high school took fewer credit hours as full-time college students than they would have had they not enrolled in a dual-credit program. That’s according to a major study on dual credit conducted on behalf of the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

Still, little national evidence exists that the significant ramp-up in offerings of college courses to high-school students is cutting down on the amount of money students spend on college.

The obstacles high-school students face trying to take their credits to the college they enroll in mirror broader challenges that college students face transferring their credits from college to college. Students who switched colleges between 2004 and 2009 — roughly 35% of college students overall during that time — lost 43% of their credits on average, according to a 2017 report from the U. S. Government Accountability Office.

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Colleges differ on how credits earned in high school can be applied

The bulk of colleges — 92% of public and 80% of private schools — say they have a policy of accepting college credits that students earn in high school, according to a 2016 survey from the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers. But in practice, whether an individual course is accepted depends on a number of factors, the survey found.

Those include the type of institution where the credits were earned, whether the receiving college offered an equivalent course and the location where the student took the course (in a high school or college classroom).

Elite colleges may not always take courses earned in high school, in part because they worry — sometimes due to a misguided bias — that community-college courses aren’t rigorous enough to put students in a position to succeed in the course sequence at their school, said Josh Wyner, vice president at The Aspen Institute and founder and executive director of the College Excellence Program.

MarketWatch photo illustration

MarketWatch photo illustration

At public colleges, the situation is far better, but still complicated. At the beginning of 2018, 30 states required their public institutions to accept college credit earned in high school, according to the Education Commission of the States, a nonprofit focused on education policy research.

But whether the courses count as general credits or towards a student’s degree program varies by institution and even by department within institutions, said Davis Jenkins, a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center for Community College Research.

Even in states where public colleges are required to accept these college credits, those credits don’t necessarily save a student from taking the required courses to complete their college degree.

In other words, even in states where public colleges are required to accept the college credits students earn in high school, those credits don’t necessarily save a student from taking the required courses to complete their college degree. In order for a student to maximize college credits earned in high school, the credits need to apply to their specific degree program, but it’s often the case that these credits transfer, but don’t actually apply towards a student’s degree.

The variation in credit-transfer policies often means that the onus is on families to figure out how to best maximize the college-credit students earn in high school.

“Depending on what universities you talk to — with everything — there’s a different answer,” said Jeff Wardle, the principal at Buffalo Grove High School in Buffalo Grove, Illinois. He’s part of a high-school district that has embarked on a major expansion of college course offerings over the past few years. “We try to educate our students and parents to be proactive,” he said.

Even so, “we’ve run into problems,” he said. In some cases, that’s because universities change their approach to transferring certain courses from year-to-year.

Lucy Hewett

Lucy Hewett

‘One of those continuing challenges’

Until universities get on the same page about how certain college courses fit into a student’s college journey, it’s unlikely students will have a seamless experience bringing the college credits they earned in high school to their full-time university.

It’s an ongoing challenge to ensure that four-year colleges and universities — especially private ones — are recognizing high-school students’ college course work, said Alan Mather, the former chief officer of the Office of College and Career Success for Chicago Public Schools.

Many high-school students are hopeful the schools will. Martin Lopez, a high-school senior taking business-focused courses at City Colleges of Chicago, described the classes as “a great opportunity,” during an interview in the fall. He anticipates the courses will help him minimize his student debt.

The classes Lopez took are offered free through a partnership between Chicago Public Schools and City Colleges of Chicago. But free college classes sometimes come with an important caveat. “I don’t want to take them if they’re not going to transfer over — that would be pointless for me,” he said.

For Jorge Barcenas-Vela, an 11th grader at Northwest Early College High School, having the credits he earned in high school recognized by his college “feels like a reward for a job that I worked hard at.” Northwest is one of several schools in El Paso designed to help students pursue their associate’s degree while in high school.

Rudy Gutierrez

Rudy Gutierrez

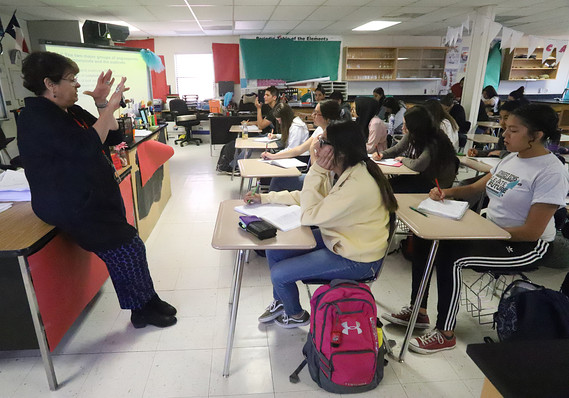

High schools are trying to provide students with guidance

For these programs to work in the way they’re often pitched to students and parents — as a tool to save money and time towards a college degree — they need to include intensive guidance for students, Jenkins said. This kind of thoughtful advising can help students avoid taking college courses at random and, instead, choose classes where they’re most likely to succeed and that will apply to their college degree.

That can mean talking with students in 9th grade and even earlier about their aspirations and how any college-level course work can fit into those plans — a high-touch level of guidance that isn’t always available, Jenkins said.

‘Advising is critical in addition to just taking courses. Students need to be helped to start to explore interests, not just take random courses.’

“Advising is critical in addition to just taking courses,” he said. “Students need to be helped to start to explore interests, not just take random courses.”

In Chicago, officials have set a goal that at least one counselor in every district-run high school has a Chicago College Advising Credential, which certifies they’ve received training from the district on how to advise students on their path to and through college, including any college-level courses they might take while in high school and how those would transfer to their college of choice.

Even with these efforts, it’s hard to guarantee students will end up in courses that help them through college and to a career faster. For one, it’s normal for students to change their aspirations several times between 9th grade and college graduation. In addition, a variety of factors outside of students’ and advisers’ control may influence the college courses students take in high school.

Courtesy of Jaime Ramirez, Jr

Courtesy of Jaime Ramirez, Jr

These students are making decisions that could steer their career choices at an even younger age, and taking college courses that aren’t suited to a student’s skill set can also have adverse consequences.

Jaime Ramirez, Jr. said that when he was a high school student at a public charter school in Chicago, he didn’t get a ton of guidance on what college courses to take. Instead, he sampled classes based on his personal interests.

(Ramirez, Jr. may not have been exposed to as much counseling because public charter schools like his aren’t included in the city’s goal to put a counselor trained in college advising in every school.)

Ramirez initially hoped to be a nurse. But after taking a biology course at Richard J. Daley College, one of the schools in Chicago’s community college system, and earning a C, he decided nursing wasn’t for him. In his senior year of high school, Ramirez took criminal justice, with the idea that he might wind up becoming a police officer. But he struggled in the course and ended up withdrawing before completing it.

When he enrolled in Daley as full-time college student the following year, Ramirez discovered that his experience taking the school’s courses in high school left him with a low starting GPA. “So that kind of sucked,” he said.

If he had the opportunity to take college classes in high school again, Ramirez said he probably would, given that it helped him narrow his career path.

But the courses didn’t do much to save him time or money on the path towards getting his associate’s degree in business. He’s already attending college for free through a combination of grants and scholarships.

Credits earned in high school can complicate college choice

Even when students follow a clear sequence and receive guidance on choosing courses that will apply to their degrees, challenges can arise.

In El Paso, early college high-school programs — which offer students the opportunity to earn their high-school and associate’s degrees at the same time — are tightly integrated with the community-college system and the local four-year college, the University of Texas El Paso.

Like Summer Baptiste, some students find themselves being pulled in one direction by their credits and in a different direction by their aspirations.

Students who earn their associate’s degree by their junior year of high school are eligible for a scholarship to take classes at UTEP during their senior year. That gives them the opportunity to earn even more free college credit — sometimes cutting down the time they’d spend as a full-time college student to less than two years.

But it also binds them to UTEP in a way that makes it difficult to consider other colleges, either outside of El Paso or even Texas, that might offer a more transformative experience.

Getty Images

Getty Images

UTEP, which is set between the Franklin Mountains and the Mexican border, offers many reputable programs and is a top-tier research university. But it’s also part of the geographically isolated community where students have spent most of their lives.

Lailah Leeser, the guidance counselor at Valle Verde Early College High School, tries to encourage students and their parents to consider all of their options and explore the idea of leaving El Paso — which is where she grew up, left for college and ultimately returned to later — at least for a time.

“I tell kids the best experience that I had in college, it was great sitting in those classes, but it was the people I met, people I would have never had the opportunity to meet if I didn’t go,” she said.

But it can be hard to sway students away from the idea of leaving their families. The family-focused Hispanic culture that dominates El Paso means that parents often want to have their children remain close by. In addition, it’s hard to pass up both the time and money savings offered at UTEP.

That dynamic is why for years Paul Covey, the principal of Valle Verde, didn’t offer students the option to finish their associate’s degree a year early and head to UTEP. “I didn’t want our kids to be trapped,” he said.

Ultimately, Covey said he worked with stakeholders to develop a system at his school where students could spend some time at UTEP, but wouldn’t earn too many upper-division credits that would be hard to transfer to another college.

“Our belief is that it’s not up to me to decide where they should go,” he said. “If they choose to go to MIT, where we’ve had kids go to, or go to Columbia where we’ve had kids go to, my job is to support them, not to roadblock the kid from doing that, even though if they go to those schools, their 60 hours here don’t transfer.”

Rudy Gutierrez

Rudy Gutierrez

Ivette Savina, assistant vice president for outreach and student access at UTEP, said in a statement that the opportunity for early college students to use the UTEP scholarship is — and has been — available to all early college students in the region.

Ultimately, more than 80% of students remain in the region, which is why the high-school system, El Paso Community College and UTEP work closely together to make sure the college courses that early college high school students take will transfer relatively seamlessly to UTEP, Savina said in an interview.

‘If they choose to go to MIT, where we’ve had kids go to, or go to Columbia where we’ve had kids go to, my job is to support them, not to roadblock the kid from doing that.’

Still, she recognizes that not all students may want to matriculate at UTEP. That’s part of the reason why Savina or the early college high-school program adviser sits down with every early college student considering taking advantage of the UTEP scholarship before they commit.

As part of that conversation, Savina says she reminds the students: “This is a unique opportunity that is really not available in any other community, but we do want to make sure that you’ve thought about this,” she said. “The idea of bouncing between schools does not match up to the idea of saving time and money.”

Savina said she also often reminds the students that even if they finish their bachelor’s degree at UTEP, they have the opportunity to leave the region for graduate school at a relatively young age, Savina said. Or they could wind up leaving for a job, particularly if they graduate with a degree in a field like engineering or finance.

“We do export our talent,” Savina said, but officials in economic development and education are thinking about how they can work more closely together “to attract those industries that support the graduates that we are producing.”

Back in Chicago, Baptiste was forced to make a tough decision at the 11th hour, but she’s happy with her choice. She’s on track to receive her bachelor’s degree in 2020, when she’s 19 years old. She plans to earn a master’s and a Ph.D following college and become a math professor.

When she finally joins the job hunt, she’s prepared to face questions about her age. “Just because I’m young doesn’t mean I can’t solve a differential equation with the snap of my hand,” she said.

Get a daily roundup of the top reads in personal finance delivered to your inbox. Subscribe to MarketWatch’s free Personal Finance Daily newsletter. Sign up here.

Add Comment