“ ‘Indexing is not a mediocre strategy. It is an above-average strategy.’”

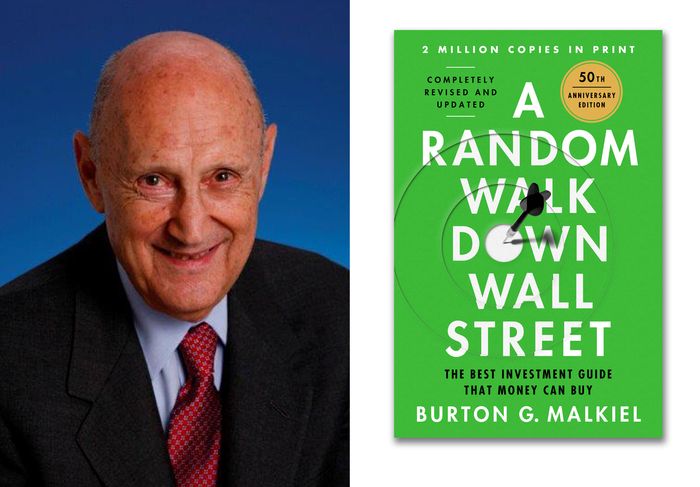

In January 1973, an investment book was published that would help change Wall Street forever. Burton Malkiel’s “A Random Walk Down Wall Street” made the then-heretical assertion that professional money managers weren’t worth their fees. Malkiel put it bluntly, stating that, “a blindfolded chimpanzee with a dart and a list of stocks” could beat Wall Street pros at their own game.

Beating the market is difficult, Malkiel explained, because the market digests all available information through what’s known as the efficient-market hypothesis. Malkiel argued that stock prices follow a “random walk” and their fluctuations cannot be predicted.

Since most stock-pickers cannot consistently beat a benchmark index such as the large-cap S&P 500 SPX, +0.14%, Malkiel, at the time a professor of economics at Princeton University, argued that investors are better off buying and holding the benchmark itself, settling for a return equal to the average. In this way, you’ll do better than active management, at a lower cost and with greater certainty.

Malkiel’s assertion was met with skepticism if not outright derison. In 1973 there was no low-cost index mutual fund available to retail investors. Malkiel advocated for the creation of such a product, but when John Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group, introduced one three years later, the money initially stayed away.

Half a century later, however, low-cost index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds are cornerstones of many investment portfolios. “A Random Walk” has become a classic must-read for investors, and just marked its 50th anniversary with another in a series of revised and updated editions. In this recent telephone interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Malkiel discussed the book’s longevity and its relevance to the current stock-market environment.

MarketWatch: Half a century after its publication, “A Random Walk Down Wall Street” is still timely and relevant — maybe now more than ever. Such longevity is rare for an investment book. Did you ever imagine it having such staying power?

Malkiel: I particularly didn’t anticipate it when the reaction from the financial community was almost uniformly negative. I had this line in the first edition that a blindfolded chimpanzee could select a portfolio as well as the experts. It was a cute remark but it rubbed some professionals the wrong way. I had some reviews from professionals including one which said this thesis, that you’d be better off with an index fund than an actively managed fund, was naïve at best and completely wrong.

The evidence over the past 50 years is such that I actually believe in the thesis even more today. Indexing is not a mediocre strategy. It is an above-average strategy and outperforms the average actively managed stock fund by about 100 basis points a year.

MarketWatch: It is difficult for investors to outperform the market average. So if your return is consistently average, by definition you will beat investors — including professionals — who fall short of a benchmark.

Malkiel: In any year there are people who outperform, but the ones who outperform the next year aren’t the same. When you compound this over 10- or 20 years, we’re talking about 90% of money managers.

I’m not saying it’s impossible to outperform. Some people have done it and may continue. But when you try for that, you’re much more likely to be in the 90% who don’t.

MarketWatch: Yet the naysaying continues, 50 years on and despite the explosive popularity of indexing. Your book was originally published in 1973, before there was an index fund. Three years later John Bogle launched the Vanguard 500 Fund, first S&P 500 index fund. You and Bogle both helped ingite a revolution.

Malkiel: The reaction to the first index fund was about the same as the professional reaction to my book: poor at best and extraordinarily negative at worst. Bogle asked the underwriters to get the first index fund started and he wanted to sell $250 million. The underwriters said we don’t think we can do 250. Let’s set it up for 150. When the books were closed it raised $11 million. It was ridiculed. It was called “Bogle’s folly.” The fund didn’t accumulate much money for at least a decade, even two. Now more than half of the money in investment funds is indexed.

MarketWatch: So much about investing has changed in 50 years, of course. What about indexing has stayed consistent?

Malkiel: What hasn’t changed is that while the market isn’t always right, it really does a remarkable job of reflecting information and to that extent is really quite efficient. Therefore you’re much better off accepting the judgment of the market and simply buying an index fund.

“ ‘It’s not that we have too much indexing; I think we still have too little.’ ”

MarketWatch: With so much money now tied to index funds, has indexing become too popular?

Malkiel: Over 50% of the money invested in investment funds is indexed. Is that too large? First of all, as the proportion of funds indexed has grown, you might think active management will do better and better, but in fact it’s doing a little worse each year. The growth in indexing has not led to active managers doing better.

And to those who say eventually there won’t be anybody left to make the market efficient, I would say that even if 95% of the market was indexed, I wouldn’t worry. It’s not that we have too much indexing; I think we still have too little. I see nothing to make me worry that the success of indexing will lead to its own downfall, as many people believe.

MarketWatch: Why are you convinced that indexing’s popularity won’t reach a tipping point?

Malkiel: The idea behind indexing is that the market will mostly get it right. If there’s a company that discovers a cure for a particular type of cancer and its stock is selling at $20 a share and this announcement should make its stock go to $40 a share, the idea of relatively efficient markets means the price will go to $40 right away.

Let’s suppose 100% of the money was indexed. The drug comes out, the stock still sells at 20. In our capitalist system, with hedge funds and private equity firms around, can you actually believe that nobody is going to step in and look for that kind of arbitrage? As long as we have free markets and somebody can buy what they want, it’s inconceivable to me that there isn’t some investor who will come in and keep buying that stock until it sells at $40 a share.

MarketWatch: Are you concerned about newer, targeted index funds that promise more bang for your buck?

Malkiel: I do question the proliferation of index funds into narrower and narrower slices of the market, and made to appeal to far more speculative investors. For instance, I think it’s terrible that we have index funds that purport to give you three times the up and down of the S&P 500. I also don’t like some of the narrow indexes that really are almost active management, because they suggest you can pick a small part of the market that is “undervalued” and do better. Using these to speculate to think you can beat the index is absolutely wrong and self-destructive.

I prefer broad-based index funds, and total stock-market index funds over S&P 500 index funds, because you ought to own everything. Since you can now buy a total stock-market index fund for an expense ratio of two or three basis points — essentially zero — that’s what I prefer.

MarketWatch: Do all the investment choices and strategies available nowadays tempt investors to ignore what the stock market can realistically deliver over time?

Malkiel: In a way investors have become smarter. But people now might be a little unrealistic about the stock market returns they ought to expect. Over the past 100 years the broad U.S. stock market has given a total return of 9%-10% a year. I don’t think the next decade is likely to do that.

There is one valuation metric that does a decent job of predicting 10-year rates of return — the CAPE ratio, the Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings multiple. It seems to explain something like 60% of the variation in 10-year rates of return. What tends to be the case is that when the CAPE is well-above average, the next 10-year rate of return tends to be on average more like 4% or 5%. When the CAPE is low, in single digits, the 10-year rate of return has been something in the teens.

Today the CAPE is around 30, which is one of the highest in history. Realistically, people ought to expect mid-single-digit returns over the next 10 years. That worries me a little. If they’re thinking about how much they need to save for retirement, how much to take out of their retirement fund to preserve its real value, investors ought to consider that projecting 9%-10% over the next decade doesn’t make sense.

Equities are still the best game in town. They are the asset class that most dependably has outlasted inflation, has done better than gold, bonds, real estate. My advice would be to be realistic and careful. Don’t blindly assume that a 10% average annual total return is written in stone. Valuations are extended now. I’m not sure how many investors understand that.

MarketWatch: If stocks give just 5% on average over the next decade after factoring for inflation, where and how should people consider allocating their money?

Malkiel: I’m not suggesting that you give up equities. I’m a great believer in dollar-cost-averaging with stocks. Frankly, if markets are very volatile, and sometimes you’re buying really low, you’ll get more than 5% from dollar-cost-averaging.

For young people starting out, save a little bit each week. Even if you never make a lot of money, you’ll have a great nest-egg when you retire. Put the lion’s share of your money into dollar-cost-averaging, into a broad based index fund. We’ve had some terrible markets over the period since the book came out. The 1970s were not a very pleasant period for stocks. The first 10 years of the 2000s markets were basically flat. But what if starting in 1978 you put $100 a month into the Vanguard 500 index fund? Today you’d have almost $1.5 million. The thing that probably pleases me the most about the book is fan mail saying, “Thank you. I’ve done exactly what you said.” My cards and letters say it actually works.

If you are older, and now have that nest egg, and earned it in a tax-friendly way, then you should not have an all-equity portfolio. I would recommend you take the required minimum distribution due within one year and put it in a one-year Treasury bond. Take the RMD you have to take out in two years and put it in a two-year Treasury. Bonds now at least give you a rate of return. For specific RMD I want Treasurys. For general investment purposes you ought to have index funds but add total bond-market funds.

MarketWatch: There’s an ongoing debate about the wisdom of the traditional 60% stock/40% bond portfolio allocation that is often a starting point for investors. Are you a fan of the 60/40 portfolio?

Malkiel: It might well be that for a retired person, 60/40 makes sense. But as a general rule, no.

In my own portfolio I do what I said in terms of the RMDs. I am not investing for myself, I’m investing for my children and grandchildren. So I’m still a heavily equity investor. If you’ve got enough to live on and you’re investing for your children and grandchildren, you don’t want 40% in bonds.

What certainly is the case is that younger investors ought to be mainly equity investors and older investors still need a lot of equity. But a much greater allocation to bonds is warranted.

“ ‘My favorite inflation hedge would be a real estate index fund.’”

MarketWatch: What advice would you give now to investors who are spooked by Wall Street’s randomness — in this case the surge in stock-market volatility and the market’s painful 2022 return?

Malkiel: Depending upon your risk tolerance, there are differences. If you can’t sleep at night because you look at your portfolio, then being 100% in equities is not for you. Sell down to the sleeping point.

That’s particularly true now because I worry about how difficult a job it’s going to be for the Federal Reserve to get us back to a 2% inflation rate. So you definitely need some assets that are likely to provide an inflation hedge. My favorite inflation hedge would be a real estate index fund, as opposed to gold. Common stocks have done a good job of hedging inflation and real estate has done better than gold. I wouldn’t like to be in long-term bonds. Particularly now I’d rather have safer ones. There’s nothing wrong with getting 4% plus from a one-year Treasury.

Volatility really helps dollar-cost averaging. For the first 10 years of the 2000s, out of the dot-com bubble, we had terrible stock markets. The market ended in 2010 where it started in 2000. Yet the $100 a month, dollar-cost-averaging investor earned 5.7% on average. It works.

One other thing to remember: Good financial results depend on doing the right thing. The right thing for me is regular investing in a broad-based index fund. It should be all-equity if you can take the risk and you’re young, or with bonds and bond index funds in retirement.

The other part of this is don’t do the wrong thing. Avoid mistakes. Don’t try the fancy shots. Just hit the ball back and you’ll be fine.

More: Here’s the only kind of financial advice people think is worth paying for

Also read: 20 income-building stocks that the numbers say could become elite Dividend Aristocrats

Add Comment