When obscure corners of the financial markets that are typically considered mundane draw outsize attention on Wall Street, it is always cause for investor concern.

That was the case last week when surging overnight borrowing costs laid bare cracks in a key Wall Street funding mechanism, which left many scrambling for cash and the New York Federal Reserve responding by injecting hundreds of billions of dollars into the financial system to restore calm.

In other words, this was no ordinary week in financial markets and more than a few investors were seeing shades of the 2008 financial crisis, reigniting decade-old nightmares of a systemic funding chaos.

‘There’s really nothing more important than the functioning and transparency of financing markets.’

“My initial reaction was fear,” said Hugh Nickola, head of fixed income at Gentrust, and a former head of proprietary trading of global rates at JP Morgan. “There’s really nothing more important than the functioning and transparency of financing markets.”

The sudden spotlight on the short-term “repo” market easily overshadowed Wednesday’s highly anticipated Fed decision on monetary policy, where the U.S. central bank cut federal-funds rates by a quarter-of-a-percentage point to a 1.75%-2% range in a divided 7-3 vote.

Rates on short-term funds, that are typically anchored to fed-funds rates, briefly became unhinged, spiking to nearly 10% on Tuesday.

See: Here are 5 things to know about the recent repo market operations

Nickola said his worries only receded after the Fed started to intervene with a series of short-term funding operations that kicked off Tuesday and totaled nearly $300 billion for the week. On Friday, the central bank tightened its grip on rates ahead of the end of the quarter, when liquidity can become scarce, by extending its daily borrowing facilities through at least October 10, and unveiling three, 14-day term operations.

The short-term rate spike also raised concerns about the potential for the funding tumult to shake consumer confidence, at a time when financial markets often are viewed as a barometer of the economy’s vitality.

Bruce Richards, CEO of Marathon Asset Management said the biggest risk to the U.S. economy was a weakening of consumer sentiment, in remarks Thursday at the CNBC Institutional Investor Delivering Alpha conference.

Richards said that while U.S. households are doing well, it would become “very worrisome” if consumer confidence starts to fade, since two-thirds of the U.S. economy is consumer-driven.

“Right now, it is corporate confidence” that is weakening, he said.

Guy LeBas, chief fixed-income strategist at Janney Montgomery Scott, also sees reason to fret due to continuing Wall Street liquidity woes that could seep into the real economy.

He pointed to three factors that still leave the money-market plumbing fragile: heavy U.S. Treasury borrowing to fund the widening fiscal deficit, a flat-to-inverted yield curve, and a regulatory environment that limits the ability of banks to absorb government debt.

LeBas thinks overnight funding operations alone won’t be enough to keep credit flowing over the longer run.

Wall Street primary dealers are tasked with helping to execute financial operations for the U.S. Treasury and the Fed and LeBas cautioned that they could run out of cash around the first quarter of next year, unless the Fed makes a series of aggressive cuts to short-term rates or launches a more permanent effort to expand its balance sheet, known on Wall Street as quantitative easing or bond buying.

“I’m not here to tell the Fed what to do,” LeBas said, adding that when banks run out of balance sheet it can lead to sales of assets like corporate debt or force banks to pull back from lending to businesses and individuals. That’s exactly what the Fed wants to avoid because a retrenchment in lending can have the effect of amplifying economic downturns.

“If the Fed does not act with rate cuts or QE, that’s the most obvious way this problem affects the real economy,” he said.

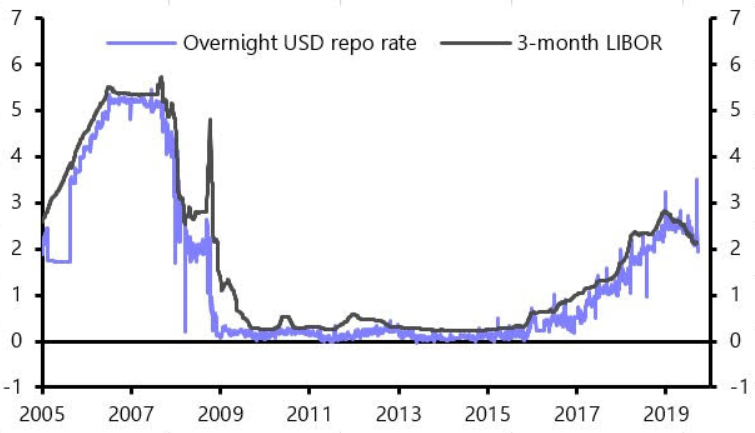

The overnight repurchasing rate, or the amount banks and hedge funds pay to borrow to finance their trading operations for a single day, peaked earlier in the week at three to four times their usual levels of around 2% (see chart below).

Capital Economics

Capital Economics The spike in borrowing costs saw investors clamoring for intervention to ease strains in funding markets. Usually, that aid comes from the New York Fed, which, because of its presence in the hub of the financial capital of the U.S., is tasked with supervising the banking system and helping to ensure financial stability among the nation’s largest institutions.

“That ability of the system to move money around and redistribute — it didn’t work the way we’ve seen in the past,” acknowledged New York Fed President John Williams in an interview on Friday, the Wall Street Journal reported.

“They walked into a situation this week where there was not enough liquidity in the system,” said Robert Tipp, chief investment strategist at PGIM Fixed Income, referring to perceptions that the Fed was slow to anticipate and react to the spike in overnight borrowing costs that took hold on Monday and accelerated the following day. “They completely were out of practice on how to perform an open market operation.” In fact, the Fed’s first intervention in short-term markets on Tuesday was aborted and had to be restarted, stoking further worries about Wall Street’s systems and process among market participants.

The Fed’s missteps come at a uniquely sensitive time for domestic and global markets, and raised serious questions about whether the blowout in short-term rates represented a signal of something more ominous crystallizing in financial markets. More than a decade ago, a seizing up of short-term markets were the hallmark of a financial crisis that saw historic Wall Street institutions Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns brought to their knees.

So, investors might be forgiven for fearing the worst as funding troubles cropped up last week.

Benchmark U.S. stock indexes have struggled to exceed all-time highs this year because fears about anemic international economic growth and an unsettling conflict between the U.S. and China over import duties has investors on edge.

On top of that, a menacing phenomenon in Treasury markets, known as an inverted yield curve, has investors worrying that a recession might be looming. Companies in the S&P 500 stock index are already in the throes of an earnings recession, a period of successive declines in earnings per share, marking the first such pullback in three years. In aggregate, companies comprising the large-cap index reported an average earnings decline of 0.35% in the second quarter, after an EPS decline of 0.29% in the first quarter.

Check out: We are in an earnings recession, and it is expected to get worse

That backdrop has made market participants particularly sensitive to news on the U.S. – China international trade dispute and hiccups by the Fed, an institution seen as one of the last lines of defense when the markets go haywire, are even more unnerving.

As the WSJ notes, the Fed hasn’t had to intervene in money markets in the past decade, up until last week, because the U.S. central bank “flooded the financial system with reserves. It did this by buying hundreds of billions of dollars of long-term securities to spur growth after cutting interest rates to nearly zero” after the 2008 financial crisis.

But despite the Fed’s stumbles, Tipp said the market still “managed to roll right through it,” even after the dramatic spike in oil prices following last weekend’s attack on Saudi production facilities.

“While this isn’t a feel-good economy, the fact of the matter is that the market looks pretty resilient,” he told MarketWatch.

For now, George Boyan, president of Leumi Investment Services, said the New York Fed’s rescue measures have been effective. He pointed to the way the effective fed-funds rate inched down to 1.90% on Thursday, or well below the upper bound of the Fed’s preferred target.

In the last few days, the fed-funds rate has either bumped at the range’s ceiling and even briefly above it after the squeeze in repo markets spilled over into the fed-funds rates, pushing the benchmark interest rates higher.

Others saw similarities to the 1980s when the Fed would carry out repo operations a hundred to two hundred times a year, said Dave Leduc, chief investment officer of Mellon’s active fixed-income arm.

“People are reacting to this as a strange thing, but they forget [the Fed’s repo operations] used to happen a lot,” said Leduc.

All that said, the S&P 500 SPX, -0.49%, the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, -0.59% and the Nasdaq Composite Index COMP, -0.80% are not far from all-time highs and corporate earnings are expected to stage a turnaround. Analysts expect things to turn positive again in the upcoming holiday period, with expectations for 1.3% EPS growth overall in the calendar year.

Next week, surveys may reveal to the extent to which consumers have been impacted by market volatility and slowing economic growth. A reading of U.S. consumer confidence in September is due on Tuesday and a reading of sentiment is due on Friday, with a host of other reports and Fed speakers on deck.

However, Wall Street may be the most keenly attuned to the internal workings of the arcane short-term funding in the hope that it resumes being mundane.

Add Comment