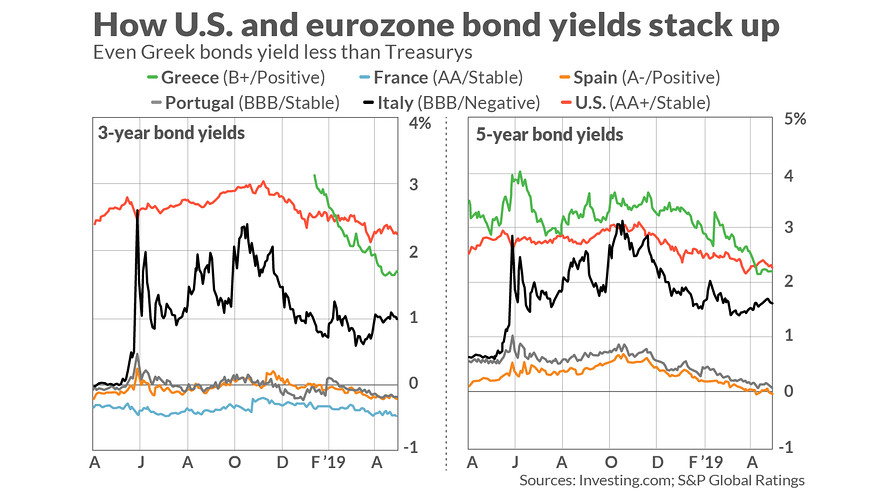

Yields on five-year Greek government bonds are lower than those of U.S. Treasurys — and have been this way for the past month.

Yes, on 3- and 5-year bonds, Greece, with its rating deep in junk territory, pays investors less than the double-A-plus-rated U.S. government does. Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and French government bonds — also lower-rated than the U.S. — offer lower, indeed considerably lower, yields than the U.S. government does, even for 10-year maturities TMUBMUSD10Y, -0.61% .

Even if we stipulate that Greece’s government is, in fact, as creditworthy as the U.S. government, why would investors accept a lower yield on the Greek bond? And why are they willing to accept the even lower yields on the bonds of other eurozone governments?

One possible reason is that they expect the euro EURUSD, +0.0625% to appreciate. Despite the low eurozone bond yields, investors may expect eventually to boost their returns by selling the expensive euros and buying cheaper dollars and other currencies. Indeed, there is some basis for such a strategy. As of late April, the consensus among analysts was that the euro will appreciate significantly over the next couple of years, and more modestly thereafter; forward markets (where buyers and sellers settle the price of a future transaction in advance) support this consensus view.

But if expectations of an appreciating euro solve the low-bond-yield puzzle, they raise another, deeper puzzle. Why would investors expect the euro to appreciate?

Such expectations would be reasonable only if one could forecast confidently that the eurozone economy is likely to grow more quickly than the U.S. economy. That faster eurozone growth would likely come with increasing inflationary pressures, which in turn would lead the European Central Bank to raise its policy interest rates. The higher short-term interest rates and more attractive investment opportunities accompanying the pickup in growth would suck money into the eurozone, raising the euro’s value.

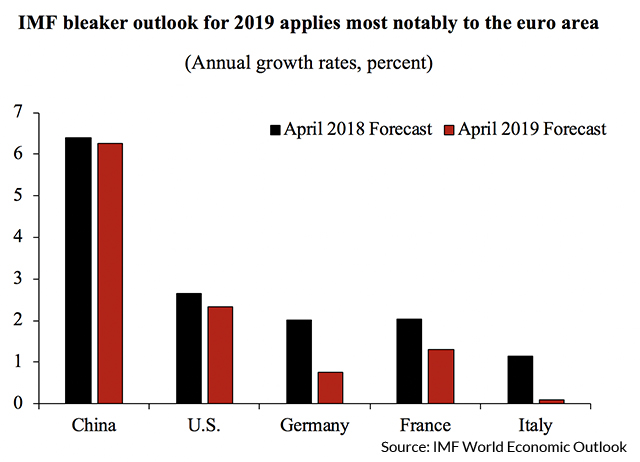

However, such a scenario is highly implausible. Current growth forecasts point worryingly in the opposite direction. The International Monetary Fund projects world economic growth to slow more markedly than it already did a year ago. Crucially, of all major economies, those in the eurozone appear to be decelerating particularly quickly.

Moreover, the IMF’s latest downgrade of the euro area’s growth prospects does not go far enough. World trade declined in the early months of 2019. For global trade to grow this year would first require clawing back that loss. Hence, the IMF’s forecast that global trade will increase 3.4% in 2019 seems utterly out of reach.

The planned U.S. move to further raise tariffs on Chinese goods can only add to the slowdown in world trade, making the IMF’s world trade forecast even more implausible. So European growth rates — tied mercilessly to international trade — will almost certainly be lower than the IMF now expects them to be.

Read: EU lowers growth forecasts amid U.S.-China trade war

If, for some reason the euro did appreciate, investors in eurozone government bonds would reap their anticipated appreciation gain. However, the already-weak euro-area economy would suffer even more, making eurozone sovereign borrowers less creditworthy and the low yields virtually impossible to maintain in the financially riskier environment.

In Yogi Berra’s words, the current exuberance is another instance of “déjà vu all over again.” We are amid the same euro-area irrationality as in July 2007, just before the start of the global financial crisis. Then, as now, French, Greek, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish government bonds offered lower yields than U.S. government bonds did. The euro was strengthening against the dollar. The exuberance was infectious. In July 2007, as the subprime crisis was claiming its first casualties, the IMF raised global and, especially, euro-area growth projections for 2007 and 2008.

Just how unrealistic that was quickly became apparent.

The euro area slowed down in the second half of 2007 and began tipping into recessionary conditions after the rescue of Bear Stearns in March 2008. Investors took a double hit. Yields on eurozone bonds rose (so prices on the bonds fell). The euro, which bought $1.56 in March, was down to $1.46 in early September, just before the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, and fell further to $1.27 by year-end. The relentless rise in bond yields and the depreciation of the euro continued as the official euro-area crisis began in late 2009.

Just as a dozen years ago, a cognitive bubble again hides the signs of trouble in the euro area.

Global policy makers have yet to acknowledge the extent and consequences of the economic weakness manifest in the fall of world trade. Policy makers also underplay the financial risks. They emphasize the decline in government debt ratios and banks’ nonperforming loans from their peaks reached during the euro-area crisis. They fail to note, however, that these vulnerabilities are at present distinctly higher than they were in mid-2007 for virtually all eurozone countries. Government debt ratios are almost everywhere considerable higher. While banks have more capital, they also have higher nonperforming-loan ratios, which likely understate the latent risks embedded in borrowers who are surviving on unusually low interest rates.

Making matters worse, while in mid-2007 eurozone authorities had policy space but made poor use of it, now they have no room for monetary stimulus and little effective possibility of fiscal stimulus. On monetary policy, the ECB has reached the end of its rope. More bond purchases through a renewal of the quantitative easing program is politically impossible at this time, as “northern” eurozone governments worry that the ECB may be left holding debt that may never be repaid. For the rest, serious internal divisions exist within the Governing Council on proposals to offer dubious incentives to encourage bank lending.

The ECB may ultimately take half-measures although, as always, only when matters have become distinctly worse — at which point taking the measures will likely be pointless. In the riskier environment, banks will either pull back on lending or charge higher risk premiums.

On fiscal policy, even governments that have low debts and fiscal deficits are unlikely to pump up their economies through fiscal stimulus. Austerity is a badge of identity in the eurozone.

Today’s cheer in eurozone financial markets — typical of the final stretch before the bubble bursts — obscures a steadily weakening economic foundation atop which sit financially fragile governments and banks. Spurred by complacent policy makers, analysts and investors ignore the big picture underlying the broad economic downturn since the middle of 2018. The U.S. economy has been and will continue to come off its sugar highs; China’s growth is inevitably slowing and Chinese authorities — fearful of further inflating their alarming financial bubbles — will be unable to contain that deceleration with significant stimulus packages. The optimists point to hopeful signs: the global economy will “rebound” in the second half of 2019, they say. However, there is no good reason to anticipate more than a short-lived rebound.

Instead, the likelihood is high that, reacting to an unexpected financial shock or persisting bad economic news, the current ultralow eurozone yields will rise quickly, dragging the economies of many member states down and raising fears of default, especially in Italy. The financial and trade interdependence between euro member states will amplify the stresses. Investors will seek even higher yields, triggering an uncontrollable downward spiral.

The right question today is not why the eurozone will have a crisis. Rather, the right question is why won’t the eurozone have a crisis soon.

Now read: Germany is a diminished giant, and that spells trouble for Europe

Ashoka Mody is the Charles and Marie Robertson Visiting Professor in International Economic Policy at Princeton University and previously was a deputy director of the International Monetary Fund’s European Department. He is the author of “EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts.”

Want news about Europe delivered to your inbox? Subscribe to MarketWatch’s free Europe Daily newsletter. Sign up here.

Add Comment